The latest breakthrough for preventing this awful disease

—-Important Message From Our Sponsor—-

3 secrets to getting more head (this makes her WANT to go down on you)

There’s nothing better than when a beautiful woman puts you in her mouth…

…and it’s even better when she’s really into it!

I used to think it was virtually impossible to convince a woman to go down on me more often…

…until I discovered how much women truly love giving passionate BJs to the right sort of guy…

…the sort of man who knows how to make her WANT to give you more head in the first place…

———-

Using daffodil flowers to fight Alzheimer’s

Galantamine is an alkaloid isolated from several flower varieties, including the daffodil and the common snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis).

This classic effect of this treatment is to inhibit cholinesterase, the enzyme primarily responsible for degrading acetylcholine.

Inhibiting this enzyme prevents the hydrolysis of acetylcholine, and whatever is spared can be used to enhance cognition.

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized on the molecular level by a few things:

Neurofibrillary tangles, β-amyloid deposits, and reduced acetylcholine receptors all define this condition.

‘Impairment of cholinergic function in AD contributes to the cognitive deficits that are characteristic of the illness.’ ―Raskind

Cholinesterase inhibitors are commonly used to treat Alzheimer’s disease for these reasons, and are in fact the only class of treatments FDA-approved in doing so.

Included in this class are just three treatments which can be legally given out, namely: donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine.

(The treatment tacrine had formerly been included in this list but was discontinued on account of hepatotoxicity.)

Of this set, only galantamine is an all-natural compound and exhibits the safety profile you’d expect from such.

All three treatments have a comparable potency and are used in the 10 to 25 milligram range, per day.

This is despite the fact that galantamine is the weakest of the three at inhibiting cholinesterase, which implies some other mechanism of action.

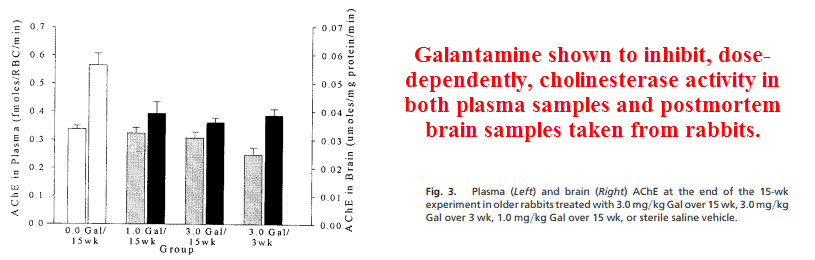

The doses of galantamine consistently shown to improve cognition are expected to yield only ~10% brain cholinesterase inhibition (Thomsen, 1991).

Because galantamine works as well as the other treatments, if not more so, there must be something else to it…

This is in fact the case, and galantamine is also a strong modulator of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (Samochocki, 2003).

This other effect of galantamine is actually quite strong.

This treatment is technically an allosteric modulator of acetylcholine receptors, functioning in a way not unlike benzodiazepines at GABAA receptors.

Allosteric modulators don’t actually activate receptors themselves, yet do potentiate the responses of other ligands.

This effect can be substantial with certain molecules such as oleamide, for instance, which is capable of increasing the response of .1 μM serotonin at the 5-HT1A receptor at only a 1μM concentration (Boger, 1998).

The potency of this natural metabolite — derived from oleic acid and ammonia — is so great that it’s active through the nanomolar range.

You could almost say that oleamide is more serotonergic than serotonin itself.

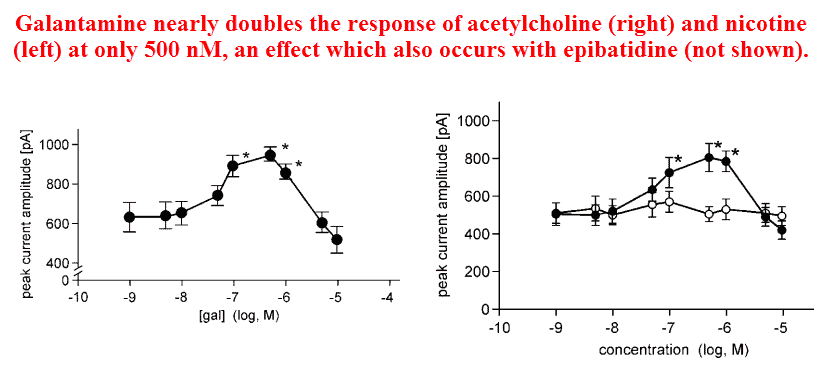

Galantamine is just as potent as any allosteric treatment on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.

Galantamine begins working at around 100nM, giving it comparable potency to oleamide on 5-HT1 and diazepam on GABAA.

So in addition to galantamine being the only all-natural treatment approved, and the safest, it is the only one with dual functionality.

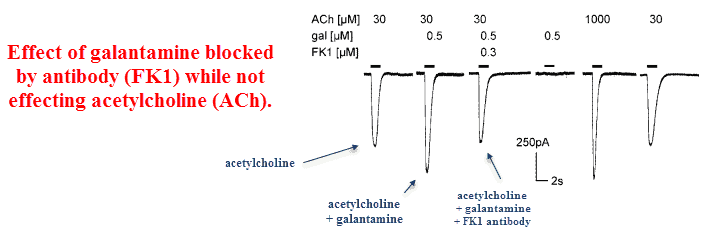

‘The amplitudes of currents produced by acetylcholine plus galantamine (30 and 0.5 μM, respectively) were similar to those of currents evoked by 1000 μM acetylcholine alone.’ ―Samochocki

And this also means that galantamine is a prime candidate for being a “nootropic treatment,” despite not generally being considered such.

The fact that it inhibits cholinesterase and also modulates acetylcholine receptors makes its inclusion as one all but certain.

All of this has been proven.

Although there are treatments that perform each of galantamine’s two separate functions individually, the cumulative results of the studies below suggest galantamine has unparalleled activity as a single agent.

Although there’d been studies before this point using galantamine on acetylcholine receptors, yet this had been the first one to investigate the interaction in greater detail.

They had discovered that galantamine is an allosteric potentiating ligand (APL), a molecule that increases the response of an agonist by binding to a separate site on the receptor.

The word allosteric is a Greek compound word that roughly translates into “other site.”

This specific function of galantamine had been proven by using an antibody specific to the “APL site,” the addition of which had blocked galantamine’s response but had no bearing on those induced by nicotine and acetylcholine.

Galantamine also did not compete with nicotine, acetylcholine, or epibatidine.

These findings further suggest that galantamine binds to a separate site than the classic agonists.

Yet on account of galantamine being capable of potentiating the response of cholinergic agents in ultra-low concentrations, it must be considered something…if not a true “agonist.”

And it is.

Galantamine is an official allosteric modulator of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.

This subtyping matters, as muscarinic acetylcholine receptors are what cause most of the side effects observed with excessive acetylcholine levels.

Since all common nicotinic treatments are selective to that receptor, it is generally only cholinesterase inhibitors and muscarinic agents that cause nausea and vomiting.

Because cholinesterase inhibitors act to increase acetylcholine indiscriminately, the intended nicotinic receptors are activated and the unintended muscarinic ones as well.

‘The APL action of galantamine produces a selective nicotinic cholinergic enhancement. In contrast, cholinergic enhancement by ChE inhibition always is both, nicotinic and muscarinic, with the latter enhancement responsible for most of the reported side effects of this therapy.’ ―Samochocki

Hence atropine — an antimuscarinic agent — is often used alongside cholinesterase inhibitors to block acetylcholine’s action on muscarinic receptors.

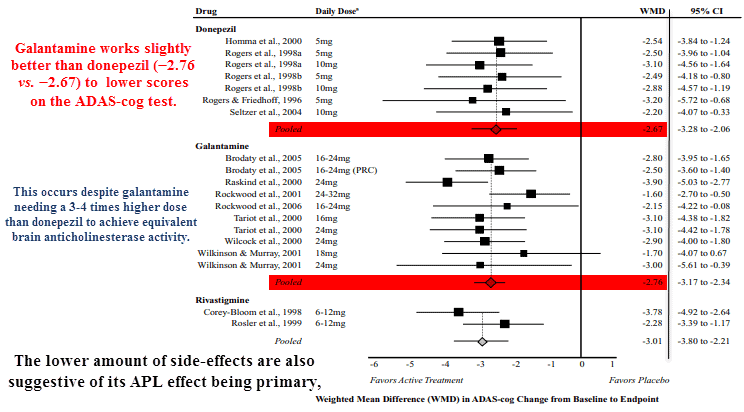

Yet galantamine is a relatively weak cholinesterase inhibitor, and because it works at the same dose as donepezil you’re nearly forced into assuming the APL effect is primary.

These chemists had also used all of the five muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes (M1-M5), and had discovered that galantamine has essentially zero activity on every one of them — even at massive concentrations (1000μM).

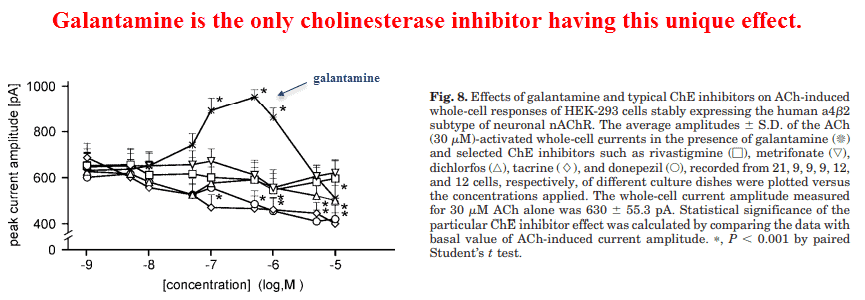

They had also shown that all other cholinesterase inhibitors besides physostigmine do not have this secondary APL function on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR).

Neither donepezil, rivastigmine, tacrine, metrifonate, and dichlorvos act as allosteric potentiating ligands (APLs).

This demonstrates the uniqueness of galantamine, a selective nicotinic agent that synergizes with itself by increasing the acetylcholine it later potentiates.

As an allosteric potentiating ligand, this treatment does not compete with primary nicotinic agents yet greatly amplifies their response.

This means that it belongs to a small class that would synergize with, and not compete against, both primary nAChR ligands and other cholinesterase inhibitors.

‘In contrast, galantamine (0.5 μM) enhanced by 50 to 60% the response to nicotine of human 42 nAChR-expressing cells.’ ―Samochocki

This fact is very important as nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) are central to cognition, and their deficiency in Alzheimer’s is thought to greatly contribute to the condition.

Since nicotine is the eponymous ligand of this receptor type, it should be no surprise that smoking has been consistently found protective against Alzheimer’s disease (Nitta, 1994).

The correlations are strong but aren’t perfect, and this could be because many separate forms of dementia are now grouped under the heading of “Alzheimer’s disease.”

Nicotine probably cannot be expected to work in all cases, specifically those caused by neurofibrillary tangles.

Neurofibrillary tangles appear, on all counts, to be a permanent inclusion body induced by aluminum ions (Al3+).

Beta-amyloid deposits are another issue altogether, yet there’s reason to suppose they are caused by low sulfate groups (SO42−) — in turn caused by sulfate depleting-treatments such as acetaminophen (Heafield, 1990).

‘nAChRs are found in brain areas that are important in the control of cognition and memory, such as the cerebral cortex and hippocampus.’ ―Samochocki

Yet even in patients having unrelated problems you’d still expect cholinergic agents to improve dementia, at least to some degree.

These treatments are what most consistently improve learning in rats, rabbits, monkeys, and humans.

For this reason you’d expect a treatment of this type, besides treating dementia, would also be also studied in relation to learning in general.

This treatment certainly has, and galantamine can improve learning acquisition in monkeys (Schneider, 2003) and in rabbits (Woodruff-Pak, 2001).

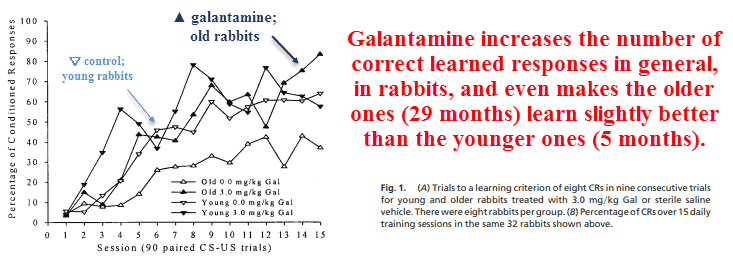

This study had tested galantamine under a rigidly-controlled learning paradigm in rabbits at a dose of 3 milligrams per kilogram (b.w.)

This dose is about tenfold higher than what humans generally take — i.e. about 0.3 mg/kg — yet since rabbits have a faster metabolism than people relative to their size, treatments are more rapidly eliminated in that species.

Regardless of this fact, the higher dose used demonstrates its safety.

They found beneficial effects everywhere they looked.

In the learning paradigm, galantamine made older rats perform at least as well as the younger ones.

Galantamine has dose-dependently decreased the number of trials needed to learn, demonstrating a beneficial effect even at 1 milligram per kilogram (b.w.)

This treatment also shortened the action response time, a classic effect of cholinergics, and expectedly reduced acetylcholinesterase activity in the brain and plasma.

They also demonstrated an increase in epibatidine binding, a nicotine-like treatment that powerfully binds to acetylcholine receptors.

This means there was either: (1) enough residual galantamine in the homogenized brain samples to exert allosteric effects, or (2) this treatment actually increased receptor synthesis just as nicotine has been shown to do (Perry, 1999).

Although the experimenters had known about galantamine’s APL effects at the time of publication, they chose to explain increased epibatidine binding as a consequence of receptor density.

‘These findings are consistent with a report that also demonstrated a similar effect of chronic Gal therapy on nicotinic receptor density. […] Taken together with the results of the current study, these data suggest that chronic Gal therapy can effectively and consistently increase the density of nicotinic receptors in selected brain regions that are involved in learning and memory.’ ―Woodruf-Pak

Either way, this is indisputably another “feather in the cap” for galantamine.

Considering just how well they’ve been associated with cognition in general, increased brain acetylcholine receptors are a good thing no matter how they’re induced.

Patients with Alzheimer’s disease generally have, on average, a reduced amount of nicotinic receptors compared to age-matched controls (Nordberg, 1986).

This is probably why smoking has been shown preventative, and is the rationale for the use of cholinesterase inhibitors to treat the condition.

‘Old rabbits treated with galantamine had the highest level of nicotinic receptor binding.’ ―Woodruf-Pak

As one of the few FDA-approved treatments used for this indication, galantamine has obviously not been neglected in treating dementia.

However: studies show that when placed head-to-head, galantamine works at a dose lower than expected from its relative cholinesterase potency (Hansen, 2008).

Galantamine is also available over-the-counter, and undoubtedly has a better safety profile than both tacrine and rivastigmine (Hansen, 2008).

So whether a person is aiming to stave-off dementia or to simply improve focus, galantamine is a safe natural compound that’s worth considering.

‘There is a large body of evidence to indicate that nicotinic ‘treatments’ indeed affect learning and memory. Nicotine and other nicotinic agonists can improve cognitive and psychomotor function, whereas nicotinic antagonists lead to cognitive impairment. Moreover, the incidence of AD in smokers is lower than that in non-smokers which may relate to the increased nAChR expression levels observed in the brains of smokers.’ ―Maelicke

‘Thus, if the therapeutic effects in AD of the three ‘treatments’ were exclusively determined by their ChE inhibitory activity, rivastigmine should be more potent than donepezil, which should be more potent than galantamine. In reality, however, this order does not apply, suggesting that, at least in the case of galantamine, a mechanism of action other than ChE inhibition must play a role.’ ―Samochocki

—-Important Message—-

Suspicious white powder — they stopped me at security

The TSA chaps thought this white powder was suspicious…

But once I explained it to them — that this white powder has AMAZING natural health benefits — they were happy to let me board my plane.

And now the TSA guys are all using this white powder themselves.

Here’s the “suspicious” white miracle powder that almost got me thrown off my airplane.

———-

Samochocki, Marek. "Galantamine is an allosterically potentiating ligand of neuronal nicotinic but not of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors." Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (2003) https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Christoph_Ullmer/publication/10845808_Galantamine_Is_an_Allosterically_Potentiating_Ligand_of_Neuronal_Nicotinic_but_Not_of_Muscarinic_Acetylcholine_Receptors/links/00b49524848c28d6af000000.pdf

Woodruff-Pak, Diana. "Galantamine: effect on nicotinic receptor binding, acetylcholinesterase inhibition, and learning." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2001) https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/98/4/2089.full.pdf

Hansen, Richard A. "Efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis." Clinical interventions in aging (2008) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2546466/pdf/cia-0302-211.pdf