Tell her this naughty bedtime story to get her wildly aroused…

—-Special Message For Men—-

Get ready for her breathing to quicken…

…watch as her eyes dilate to dark pools of lust…

You’ve just unleashed her inner animal…

…and she’s about to sink her claws into you!

Tonight Only: FREE St. Patrick’s Day gift when you try my Bigger, Badder, Better protocols for just $1

Just go here and use the special code: GREEN

———-

Is arthritis caused by this simple bacterium?

Of the many causes of joint pain, reactive arthritis could perhaps be the most common.

This was originally defined as a form of arthritis caused by bacteria, but without any being found physically within the joints (Sievers, 1972).

In this way it differs from septic arthritis, the type in which bacteria can be isolated from the joints.

Reactive arthritis is classically associated with infection by Salmonella, Yersinia, Mycobacterium, Clostridium, Brucella, and Shigella species.

It is called “reactive” because the immune system reacts to the bacteria present in the intestines as it should, but also the joints in distant locations for some odd reason.

Thus antibiotics have no immediate effect on reactive arthritis and paradoxically, they’ve even been shown to cause it.

This is because taking penicillin, for instance, can upset normal bacterial flora leading to hyperinfection of β‑lactam resistant arthritogenic bacteria — such as Clostridium difficile (Boice, 1994).

“The term ‘reactive arthritis’ was introduced in 1969. It was defined as arthritis, which develops during or soon after an infection elsewhere in the body, but in which the microorganism does not enter the joint cavity.” ―Hannu, 2001

The process by which bacteria localized exclusively in the intestine can cause arthritis in the joints had eluded researchers for decades.

Eventually, though, enough evidence was compiled to know how it occurs.

The science leading towards the full understanding of this arthritis type had been initiated years before it’d even been defined.

It was originally known as adjuvant arthritis, and only later could it be shown the two were fundamentally the same:

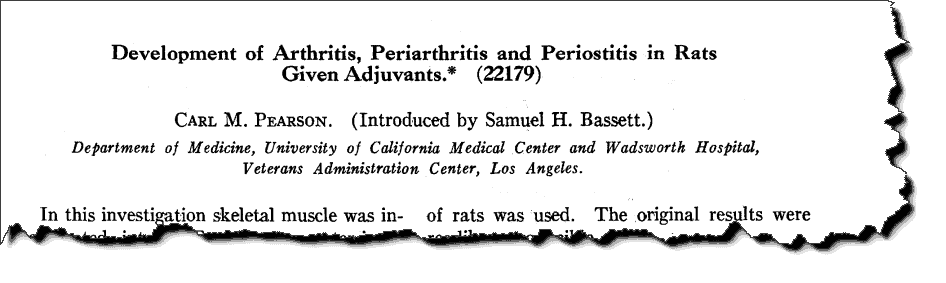

As early as 1956 it was shown that injections containing “adjuvants,” in this case those containing Mycobacterium phlei, could induce arthritis in rats.

Arthritis had occurred in 67% of the rats injected with bacteria, despite the fact that they’d all been killed, thus ruling‑out any possibility of an infectious mechanism — i.e. septic arthritis.

Arthritis didn’t occur when the carrier oil was injected alone.

But when Mycobacterial toxins were added, arthritis occured so reliably that the condition was given a new name — adjuvant arthritis.

This name derives from the fact that Mycobacterium tuberculosis in oil is called “complete Freund’s adjuvant,” ostensibly because of its powerful immunostimulatory nature.

So this was obviously a peculiar effect of certain bacterial toxins…

The suspicion that it was an autoimmune effect was convincingly proven thirteen years later (Whitehouse, 1969).

White blood cells from rats made arthritic by injections of Mycobacteria were found to induce, upon transfer, a similar form of arthritis in other rats.

This shows that not only were immune cells causing the arthritis, but immune cells with long memory (e.g. T‑cells, B‑cells).

The next major finding came 14 years after that with the demonstration that an isolated T‑cell line reactive towards Mycobacterium tuberculosis could transfer arthritis from rat to rat (Holoshitz, 1983).

This isolated T‑cell line was later shown to be composed of three individual T‑cell lines, only one of which was arthritogenic (Holoshitz, 1984).

This refined line of cells was used for subsequent research.

“Adjuvant arthritis can be induced in susceptible strains of rats by a single intradermal injection of complete Freund’s adjuvant containing killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis in oil.” ―Holoshitz, 1984

So up to this point, these researchers had a stable T‑cell line that caused arthritis, but no idea about what comprised the antigen or autoantigen.

Bacteria and joints both have a multitude of proteins, any two of which could theoretically cross‑react.

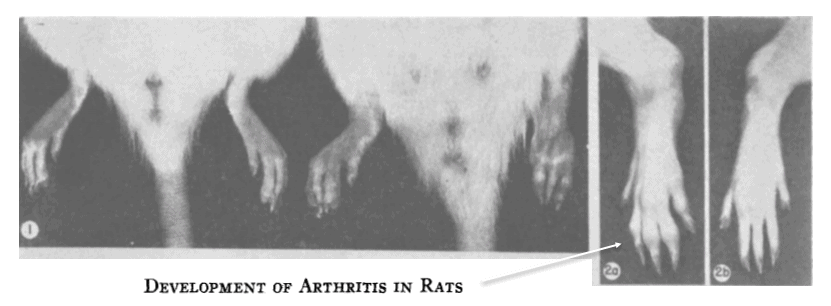

A breakthrough had come a year later when it was shown that this arthritic T‑cell line would not only attack Mycobacterium, but also cartilage proteoglycans (van Eden, 1985).

These arthritis‑inducing T‑cells were also reactive towards human synovial fluid and chondrocyte culture supernatant, two fluids expected to contain soluble proteoglycans.

Yet despite all these findings, there was no indication at this point that any of it had relevance to human arthritis.

Did this actually occur in people that had been infected with bacteria?

Or was this just an unusual effect peculiar to rodents?

Compelled by this very question, the same researchers were able to provide an answer just one year later:

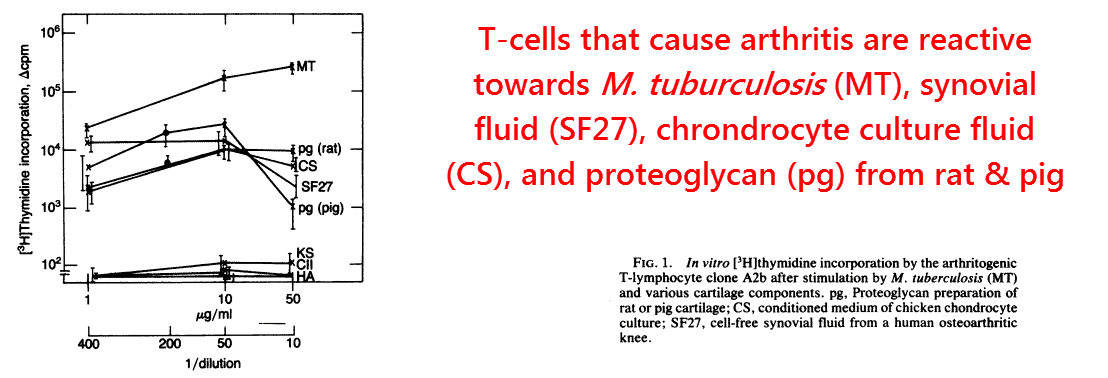

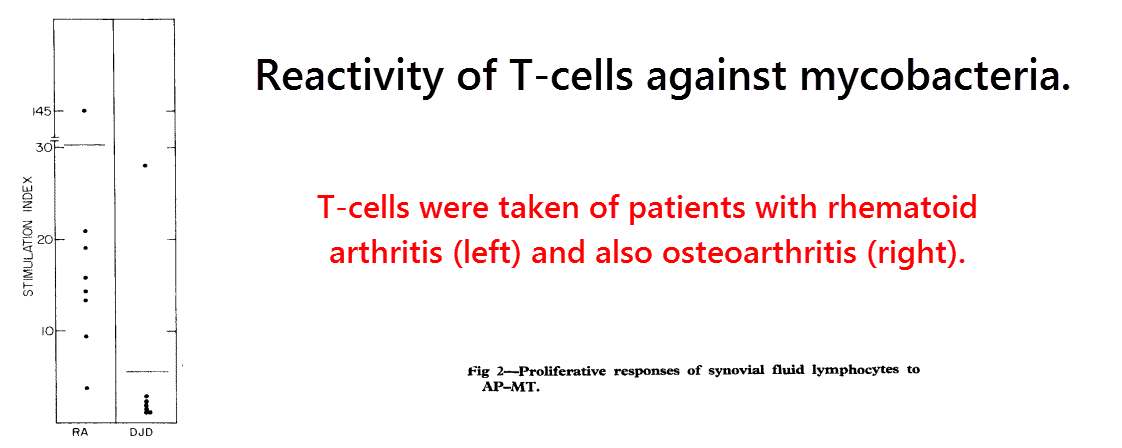

This same core group of Israeli researchers had extracted blood and synovial fluid from 34 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and isolated their T‑cells.

Using cells from each of their patients, they stimulated them using mycobacterial antigens and used [3H]‑thymidine uptake to determine the response.

“Adjuvant arthritis is a model of arthritis that presents with a pathological picture similar to that seen in rheumatoid arthritis.” ―Holoshitz, 1984

They found that plasma T‑cells from practically all of the 34 patients with rheumatoid arthritis reacted to the antigens, thus implying previous bacterial exposure.

The same was true of the T‑cells derived from synovial fluid:

All of the T‑cell samples from the rheumatoid arthritis group (right) reacted strongly, but only one from the control group (left) did.

The control group was actually composed of patients with other joint disorders, so there’s a good chance the sole patient that reacted was misdiagnosed previously…

And therefore were truly suffering from rheumatoid/reactive arthritis…

Or they had two different joint conditions simultaneously.

Be that as it may, this study provided convincing evidence that bacteria infections likely underlie many cases of rheumatoid arthritis.

These researchers also showed crossreactivity between M. tuberculosis and cartilage proteoglycans by, in this case, using antibodies with similar affinity for both (7.8 versus 7.3).

So shortly after this study was published, adjuvant arthritis was no longer just another form of experimental arthritis.

It was now a real clinical entity, and was simply reactive arthritis administered through a different route.

Consistent with this idea is the fact that arthritis is a common complication of BCG vaccines, which also contains inactive M. tuberculosis (Torisu, 1978).

Yet still the precise antigen and autoantigen were not known by the late ’80s.

There are thousands of individual proteins of M. tuberculosis that could theoretically cross‑react with any of the dozens specific to the cartilage.

Yet the increasing importance of “adjuvant arthritis” ensured that the next breakthrough was quick to follow.

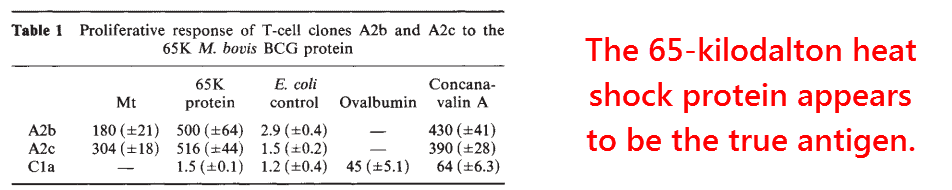

An important piece of the puzzle came when the mycobacterial 65‑kDa heat shock protein was shown to stimulate the arthritogenic T‑cell line more potently than the whole bacteria (van Eden, 1988).

The unusual reactivity of 65‑kDa heat shock protein was confirmed in later studies, and makes a good candidate for being the antigen.

This is because the 65‑kDa heat shock protein is the most well‑conserved protein among bacteria and many species are known to induce reactive arthritis.

Some of these species include Yersinia enterocolitica, Clostridium difficile, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Salmonella typhimurium, Shigella flexneri, Brucella melitensis, etc.

Following from this new finding came reports of arthritic patients having antibodies against the 65‑kDa heat shock protein (hsp65) in their bloodstream and synovial fluid, some of which were published later the same year (Res, 1988).

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis have, on average, more antibodies against M. tuberculosis hsp65 than patients with tuberculosis (Rook, 1988).

Similar reactivity has also been observed from T‑cells taken from patients with reactive arthritis (Gaston, 1989), one of types already known to be caused by bacteria.

It’s also been reported that patients with reactive arthritis caused by Yersinia enterocolitica and Chlamydia trachomatis react strongly to hsp65.

Patients with Lyme arthritis, a septic type, however, do not (Mertz, 1998).

So the 65‑kDa heat shock protein is certainly the best candidate for being the antigen behind autoimmune arthritis, but what exactly does it cross‑react with in the joints?

This million‑dollar question was investigated the moment hsp65 was singled out.

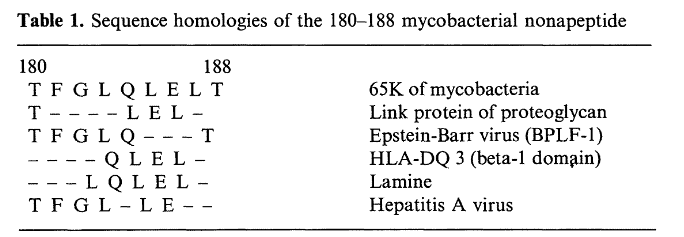

Researchers had initially pinpointed a nonapeptide of hsp65 between amino acids 180-188 as it caused the greatest response on T‑cells of all tested, yet the response wasn’t as good as the entire hsp65 protein.

Despite the relatively low reactivity of this peptide fragment, a large amount of research was focused on it.

After a thorough homology search, its closest relevant match was found to a proteoglycan link protein in which only 4 of the 9 peptides were identical. (van Eden, 1989).

Surely, we better hope that our immune systems are more specific than that.

We’d get autoimmune diseases from pretty much anything if two proteins that dissimilar could cross‑react.

A much better fit can be found between hsp65501–508 and aggrecan — a cartilage protein — with 6 out of 8 amino acids being identical:

LQNSAIIA [Aggrecan]

LQNAASIA [Heat Shock Protein 501–508]

This sequence of aggrecan being the autoantigen seems even more likely when considering that it’s found within the most exposed area of the protein, the G1 domain (Li, 2000).

Thymus cell lines from hsp60‑injected rats have also been shown to cross‑react with this G1 domain (Zügel, 1995), and T‑cells taken from arthritic patients have been shown to respond specifically to its LQNSAIIA region (Zhang, 1998).

“We recently discovered that PBLs of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis patients often respond to G1, and that G1-specific T cells can be found in the peripheral blood and synovial fluid of rheumatoid arthritis patients, including T cells recognizing epitope 150–169.” ―Zhang, 1998

What also makes aggrecan the most probable target is that it’s entirely specific to cartilage while human hsp60, another suspected autoantigen, is not.

Human hsp60 can be detected in the serum of normal adults at a concentration of 1.7 μg⁄mL(Pockley, 1999), and also at 16.7 ng⁄mL in the plasma of children with septic shock (Wheeler, 2007).

So even if T‑cells which cross‑react with human hsp60 were present in all cases of rheumatoid arthritis, you probably wouldn’t expect them to congregate at the joints.

In fact, the presence of anti‑hsp60 T‑cells in arthritic cases has been investigated yet only found at the prevalence of 18%.

Contrast this with the 64% that tested positive for reactivity towards Mycobacterial hsp65 (Pope, 1992).

Moreover, the 18% of T‑cells that did respond to human hsp60 did so 13 times less strongly than Mycobacterial hsp65.

All of this of course means two things:

- Thymus cells reactive towards Mycobacterial hsp65 are commonly found in arthritis

- Thymus cells don’t strongly cross‑react with human hsp60, but with something else… .

So the target autoantigen in reactive arthritis, and in some cases of rheumatoid arthritis, is probably aggrecan.

This is a cartilage protein and has a region nearly identical with an octapeptide in bacterial hsp65.

So what’s the best way to reverse reactive arthritis?

The answer, of course, is to find the bacteria and to destroy them.

The bacteria are most likely to be found in the intestines, lungs, gums, and teeth.

“Of the respiratory pathogens, Chlamydophila pneumoniae can be involved in nearly 10% of patients with reactive arthritis.” ―Hannu, 2011

After these bacteria are gone, cases of reactive arthritis are known to resolve spontaneously within 3 t o 5 months (Hannu, 2011).

This short timeframe isn’t only clinical observation, but also the definition.

Anything that lasts beyond that time is classified as rheumatoid arthritis.

Although reactive and rheumatoid forms of arthritis are medically defined as being different and mutually exclusive, their similarities would suggest that the latter could be a chronic type of the former in about 64% of cases (Pope, 1992).

This corresponds favorably with the 42% prevalence of collagen type‑II autoantibodies found in rheumatoid arthritis (Clague, 1980), as this approximates the remainder of patients without aggrecan autoreactivity.

Hence, these two subtypes together can explain all cases of rheumatoid arthritis: 64% + 42% = 106%

Incidentally, the cause of collagen type‑II autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis is “officially” unknown, but they could have a dietary nature.

It’s been shown that collagen type‑II from chicken, but not beef or fish, is immunogenic to humans, so this could be the autoantigen.

Collagen type‑II is only found in cartilage, so if you don’t eat mechanically‑deboned chicken, or chew on animal bones, you’ve no need to worry about arthritis under this view.

—-Important Message for Men With Arthritis—-

This “manly” element erases joint pain while naturally boosting testosterone

In the 1960s, Dr. Rex Newnham discovered a natural white powder with tremendous benefits… I call it the Manly Element.

Just a tiny pinch of this powder cured Dr. Newnham’s arthritis and joint pain — and it worked for the hundreds of people he shared it with too!

And not only did it completely erase his pain, it raised men’s testosterone levels while boosting sex drive and more.

So why haven’t you heard of it before?

Once Big Pharma got wind of Dr. Newnham’s discovery, they had it banned by labeling it “dangerous.”

But I promise you, the Manly Element is as safe as table salt.

Big Pharma just doesn’t like it because it threatens their monopoly on pain treatments.

I use just an eighth of a teaspoon every day to live pain-free among many other benefits.

Discover what the Manly Element can do for you — and how to get it for cheap.

———-

[2] Holoshitz, Joseph. "T lymphocytes of rheumatoid arthritis patients show augmented reactivity to a fraction of mycobacteria cross-reactive with cartilage." The Lancet (1986) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673686900036

[3] Pope, Richard. "Activation of synovial fluid T lymphocytes by 60‐kd heat‐shock proteins in patients with inflammatory synovitis." Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology (1992) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/art.1780350107

[4] Li, Ning Li. "Isolation and characteristics of autoreactive T cells specific to aggrecan G1 domain from rheumatoid arthritis patients." Cell research (2000) https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robin_Poole/publication/232771726_Isolation_and_characteristics_of_autoreactive_T_cells_specific_to_aggrecan_G1_domain_from_rheumatoid_arthritis_patients/links/0deec532307658528d000000.pdf

[5] Clague, R. B. "Incidence of serum antibodies to native type I and type II collagens in patients with inflammatory arthritis." Annals of the rheumatic diseases (1980) https://ard.bmj.com/content/annrheumdis/39/3/201.full.pdf