This one spice is showing incredible benefits for men

—-Important Message—-

If your penis is your favorite organ, this will be the most important thing you ever read

I’ve found a simple way to open up constricted, narrow arteries and improve blood flow.

This improves blood flow to the heart, the other organs, and even the male member.

And when the member is getting lots of oxygen-rich blood flow, men experience stronger, longer-lasting “rockiness”…

Think about it… blood fills up the penile chambers, expanding them…

…and this produces big, engorged vein-busting erections in men.

And as long as the blood is flowing “down there,” men can last as long as they want.

Try my new “vasodilation” discovery for yourself tonight — it’s free.

———-

This is how much cinnamon it takes to help men down there

Everybody loves cinnamon, so any claims about its benefits would be happily accepted without proof…

Yet there’s actually a good amount of evidence to back them up.

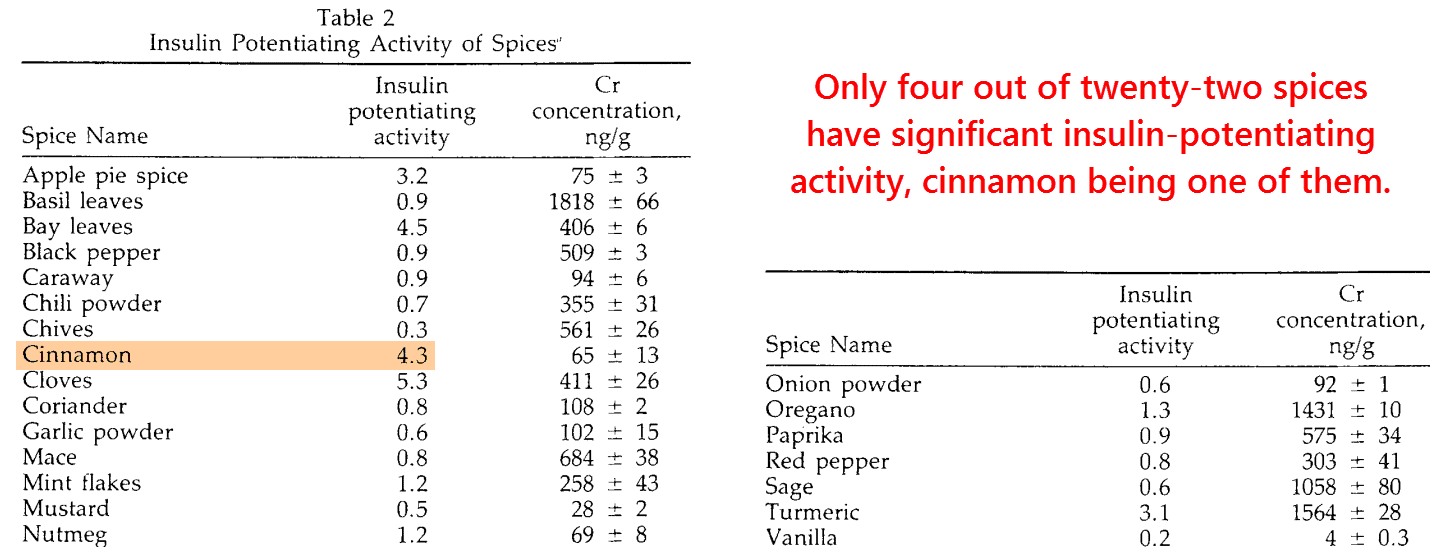

Indications that cinnamon can improve metabolism date back decades, beginning with a routine assay of 31 foods & 22 spices for insulin‑potentiating activity in vitro (Khan, 1990).

They had also measured the spices’ concentration of chromium, an antidiabetic trace element, to see if there was any significant relationship between the two.

Of course, the majority of foods had absolutely no effect, but a few spices in particular had really stood out.

These were turmeric (×3.1), cinnamon (×4.3), bay leaves (×4.5), and cloves (×5.3).

Also, having insulin‑potentiating activity was “apple pie spice,” but seeing as it’s a mixture of five individual spices it shouldn’t be grouped with the others.

The activity of pie spice likely derives from its cinnamon and clove, yet diluted by the inactive nutmeg and allspice.

The spices’ insulin‑like activity bore no relationship to their chromium content.

Now these spices aren’t traditionally known for improving diabetes, or what you could say about ginseng and banabá leaf, so this was a surprise and had stimulated new lines of new research.

These four spices have subsequently been studied on animals and people with good results, but it was cinnamon that had clearly received the most attention.

This is partially because after an in vitro study done ten years later, cinnamon emerged the undisputed winner at most dilutions tested (Broadhurst, 2000).

“Cinnamon was the most effective botanical product, and the effectiveness was maintained even at high dilution.” ―Broadhurst, 2000

At the 1∶10 dilution for instance: Ceylon cinnamon was 780% more potent than bay leaf, 889% more potent than clove, and 2,531% more potent than turmeric.

Twenty‑nine years later and there’s now enough evidence to know that cinnamon works, consistently, and also how it does so.

Cinnamon has been studied more than any other spice in this area, and there’s good reasons for this:

Based on the two early glucose uptake assays and a few rodent studies, researchers from Pakistan conducted the first human diabetes trial on cinnamon.

This was a fairly straightforward study, involving 60 diabetics given either capsules of whole cinnamon or wheat flour (placebo).

Considerable reductions in blood glucose were noted in all three cinnamon groups at forty days: a 25% reduction in the 1 gram group, an 18% reduction in the 3 gram group, and a 29% reduction in those taking six grams.

There was no real change in the placebo groups, but thankfully the wheat flour hadn’t made them any worse.

“The addition of 1, 3, or 6 grams of cinnamon to the diet led to significant decreases in serum glucose levels after 40 days.” ―Khan, 2003

The whole cinnamon spice also caused significant reductions in plasma triglycerides and cholesterol, something that doesn’t occur with the water/ethanol extracts.

This is demonstrated by the only rodent cinnamon study in which those parameters were measured (Li, 2013), and also by a human study from Germany:

This was the second clinical trial using this spice and diabetes, and was no doubt stimulated by that favorable report from Pakistan and the growing body of cinnamon literature in general.

So to either confirm or deny the hypoglycemic effect in Europeans, they gave 65 diabetic Germans an aqueous cinnamon extract for four months.

“As a consequence of the results obtained by Khan et al. with cinnamon powder, many diabetics are already taking cinnamon products even though our knowledge remains limited.” ―Mang, 2006

They noted a 10.3% reduction in blood glucose, yet no real change in lipid parameters.

This was somewhat unlike the previous Khan study.

So why is this? Why the differences in response between the whole cinnamon bark and its aqueous extract?

The standardized extract they used corresponded to one gram of cinnamon per capsule, with three taken per day, so I think we can rule out any differences stemming from dose level.

Three grams per day was the same amount used in the Khan study.

You probably wouldn’t expect Europeans to be that much different than Middle Easterners, physiologically speaking, and the same difference is noted between rat groups.

“The amount of aqueous cinnamon extract corresponded to 3 grams of cinnamon powder per day.” ―Mang, 2006

As it turns out, there’s a very simple reason for this.

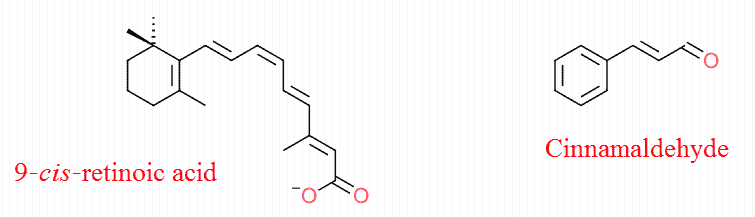

The aqueous cinnamon extract contains much lower amounts of cinnamaldehyde, a molecule highly concentrated in the essential oil fraction.

Cinnamaldehyde is the most well‑studied component of cinnamon, best known for killing bacteria and activating TRPA1 channels, thus causing warmth.

Yet recently, it’s been shown to activate RXR.

The retinoid X receptor (RXR) is the indispensable dimer partner for PPAR receptors, including PPARγ and PPARα, and they cannot be activated without it.

These are two important receptors for glucose and lipid‑lowering, with PPARγ being the target of thiazolidinediones and PPARα the target of fibrates.

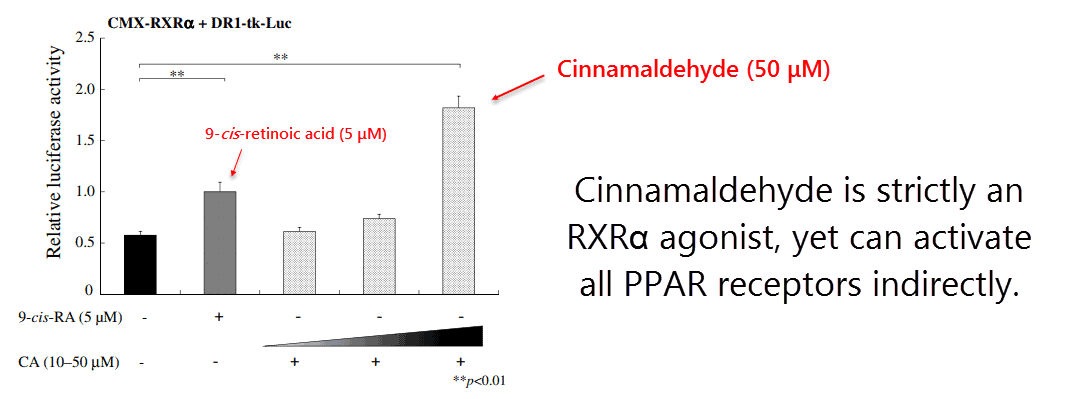

A previous study showed a cinnamon extract could activate PPARγ and PPARα to a similar degree (Sheng, 2008), an unusual property for one molecule, so these researchers investigated further.

They had confirmed by using whole cell luciferase assays that cinnamaldehyde could activate PPARγ and also PPARδ to a similar degree.

The two studies taken together would indicate that cinnamaldehyde activates three different PPAR receptors to the same extent — completely inexplicable, unless assuming that it actually activates RXR.

This suspicion was reinforced by noting that cinnamaldehyde synergizes with L‑165041, a highly potent PPARδ agonist.

Since the PPARδ-RXR dimer pair is what helps replicate DNA, having a ligand for both should have a synergistic effect.

If cinnamaldehyde was actually a PPARδ agonist instead, it’d be expected to COMPETE against L‑165041 and not synergize with it.

And finally, to confirm their suspicion they tested cinnamaldehyde on this receptor, discovering it could activate RXRα nearly as potently as as 9‑cis‑retinoic acid:

But that’s not to say that taking cinnamaldehyde is quite like taking vitamin A, as retinol is converted to 9‑cis‑ and 9‑trans‑retinoic acid only in a regulated fashion.

Moreover: the two retinoids also have activity elsewhere, such as the retinoic acid receptor (RAR) and retinoid orphan receptor‑β (RORβ).

Essential oil of cinnamon then appears more analogous to taking naringenin (Goldwasser, 2010), the weight loss polyphenol found in grapefruit.

So what about the ethanol and water extracts of cinnamon?

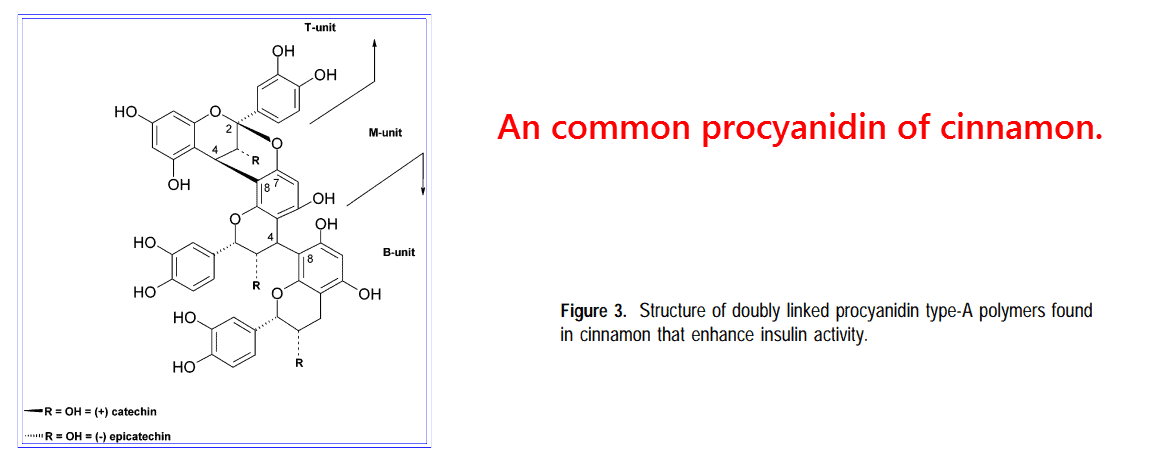

While a few groups were focusing on cinnamaldehyde and nuclear PPAR receptors, others were concentrating on insulin signalling and cinnamon procyanidins.

The procyanidins found in cinnamon are small polymers of catechin, a polyphenol, which are usually found between two and four molecules in length:

These have been shown to be responsible for the immediate effects of cinnamon, which can only occur through membrane receptors and/or cytosolic enzymes.

Although nuclear PPAR receptors eventually have antidiabetic effects, these take hours to manifest because genes must be transcribed beforehand.

For this reason and a few others, there must be another component of cinnamon at least partially responsible for its effects:

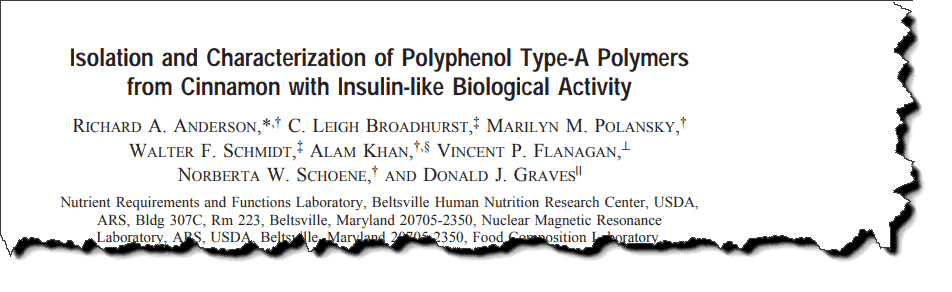

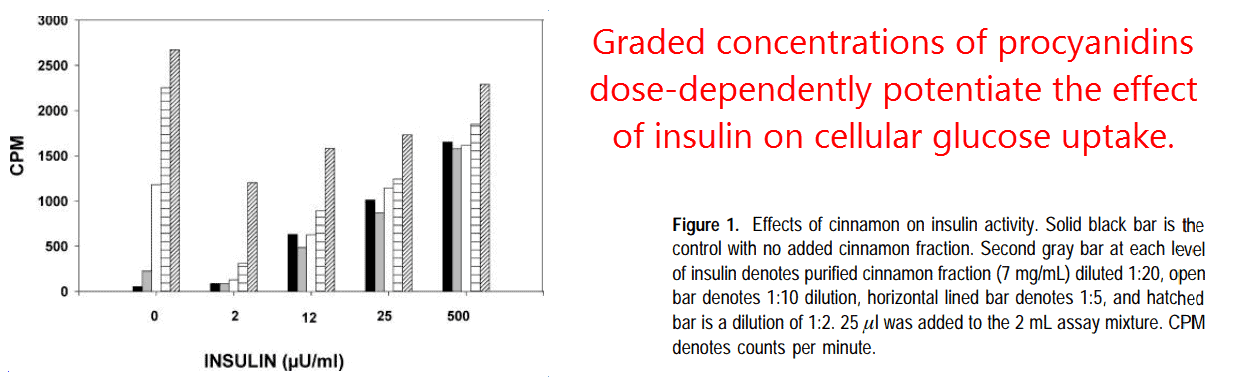

This is a follow‑up conducted by the same group of researchers who previously showed cinnamon to outcompete 48 other plant extracts (Broadhurst, 2000).

Inspired by the potent insulin‑like activity of cinnamon extracts, they decided to fractionate it further and compare each subfraction on [14C]‑glucose uptake.

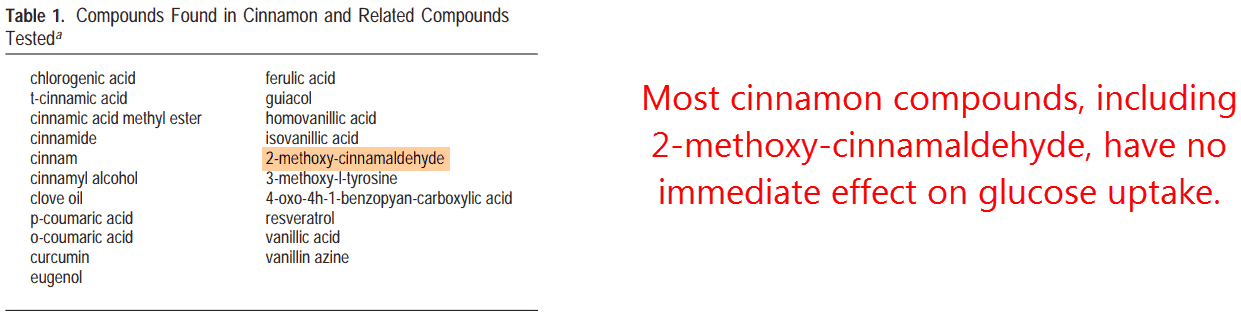

Most of the components in isolation had absolutely no effect on [14C]‑glucose uptake, with essentially all insulin‑like activity coming from just one subfraction.

And using mass spectrometry, they characterized the active agent as an A‑type procyanidin.

This was capable of enhancing insulin’s activity 20‑fold, and could even work in its absence.

So what is going on? Do cinnamon procyanidins bind insulin receptors in a way similar to the lagerstroemin, the ellagitannin found in banabá leaf (Hattori, 2003)?

Well, maybe so and maybe not.

There are many enzymes involved in insulin signalling that, when inhibited, have been shown to exert similar effects.

Yet after analyzing the other cinnamon studies, and a few on procyanidins in general, it’s easy to come to the conclusion that they’re PTP‑1B inhibitors.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase‑1B (PTP‑1B) is an enzyme that constantly acts to terminate the insulin signal by inactivating, via dephosphorylation, the insulin receptor substrate — the mediator of insulin’s signal within the cell.

For this reason, rats genetically engineered to lack PTP‑1B have enhanced blood sugar control because their insulin signals last longer.

This enzyme is therefore a prime target in diabetes treatment, and substances which inhibit it are said to be “insulin sensitizers.”

Berberine is known to potently inactivate this enzyme (Ki = 91.3 nM), most likely the reason for its antidiabetic effects.

Since so many studies had already proven beforehand that cinnamon can lower plasma glucose and enhance the insulin response, these researchers decided to focus exclusively on the mechanism.

They first proved that cinnamon worked through the insulin pathway by using wortmannin, a classic inhibitor of this.

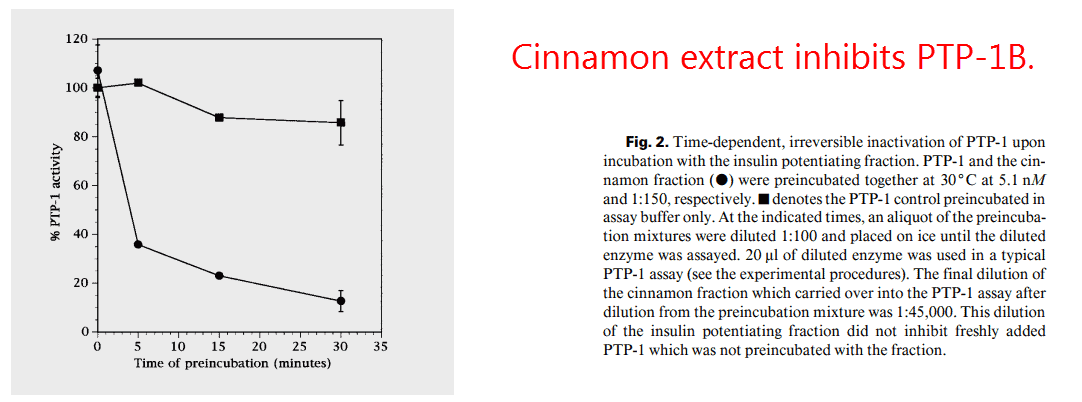

They also showed a few changes in the cellular phosphorylation state upon adding the cinnamon extract, yet knew they found their target after the PTP‑1B assay.

At a relatively modest dose, they showed cinnamon extract to directly inhibit PTP‑1B.

This is the most solid evidence so far of cinnamon’s mode of action.

There is no evidence that it can directly activate the insulin receptor, the other most likely possibility.

This is supported by a procyanidin found in cocoa beans also inhibiting PTP‑1B (Żyżelewicz, 2016).

This effect of cinnamon procyanidins is consistent with all the evidence, and can help explain everything that cinnamaldehyde cannot.

These molecules are certainly active in vivo, as demonstrated by the many rodent studies demonstrating the purified cinnamon procyanidins can lower plasma glucose (Lu, 2011).

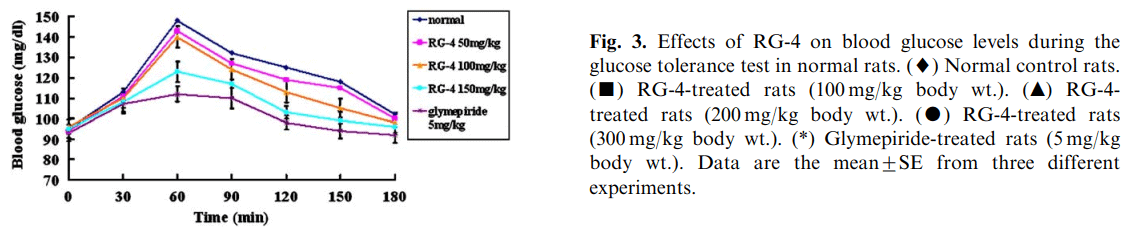

This hypoglycemic effect occurs in both normal and diabetic rats, and the procyanidins can enhance the clearance rate of injected glucose (Jia, 2009):

This enhancement of glucose clearance rate has also been reported in humans (Sauer, 2007), so the effect is official.

Cinnamon has antidiabetic effects, likely the combined result of its cinnamaldehyde and procyanidins.

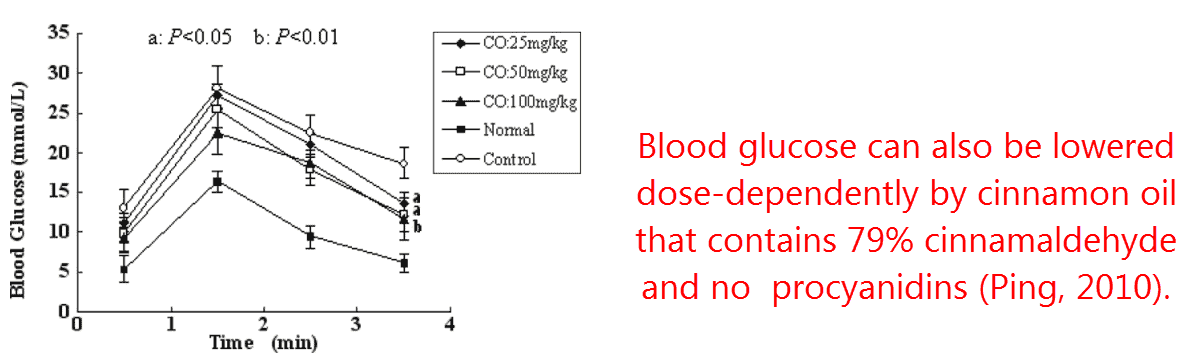

This is because cinnamon oil has also been shown to lower plasma glucose (Ping, 2010).

Cholesterol and triglycerides were also lowered in this study, another indication of cinnamaldehyde’s PPAR activity in the liver.

These two molecules help explain the disparate results from different cinnamon fractions.

This also implies that the whole spice is more effective than either fraction individually.

Yet should a person want just an insulin‑sensitizer or a general PPAR activator, then of course either cinnamon extract can be used individually — the essential oil or an ethanol/aqueous extract.

“Additionally, approximately 50 plant extracts have also been investigated in this assay, and none have shown activity equal to that of cinnamon.” ―Anderson, 2004

—-Important Message—-

These 3 solo activities work better than pills to give men long-lasting rockiness

Each one of these little solo activities gives men big, vein-busting erections that last for 30 minutes or more…

…while restoring sensitivity and sensation back into your member…

…so you feel more and more pleasure, and perform at your best every single time.

Just practice these 3 solo activities at home and see instant results.

Even if you’ve had erections problems for years.

Even if you’re 60, 70, or 80 years old.

Or, if you’re just realizing that you aren’t as rocky as you used to be and want a little extra “oomph” in the erections department.

Remember: These 3 solo activities are natural and safe, and work better than the pills.

Try just 1 of these solo activities out tonight and prepare for a BIG surprise…

———-

[2] Mang, B. "Effects of a cinnamon extract on plasma glucose, HbA1c, and serum lipids in diabetes mellitus type 2." European journal of clinical investigation (2006): http://mjota.org/images/Cinnamon_diabetes_Mang_202006.pdf340-344.

[3] Khan, Alam. "Insulin potentiating factor and chromium content of selected foods and spices." Biological trace element research (1990) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02917206

[4] Khan, Alam, et al. "Cinnamon improves glucose and lipids of people with type 2 diabetes." Diabetes care (2003) http://www.mjota.org/images/cinnamondiabcare.pdf

[5] Anderson, Richard. "Isolation and characterization of polyphenol type-A polymers from cinnamon with insulin-like biological activity." Journal of agricultural and food chemistry (2004) http://www.vitawithimmunity.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/AndersonJAgricFoodChem2004.pdf

[6] Broadhurst, Leigh. "Insulin-like biological activity of culinary and medicinal plant aqueous extracts in vitro." Journal of agricultural and food chemistry (2000) https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jf9904517