[cmamad id=”26489″ align=”center” tabid=”display-desktop” mobid=”display-desktop” stg=””]

And now couples everywhere are thanking him DOUBLE for his service…

—-Important Message From Our Sponsor—-

Vietnam vet discovers jungle food that gives men INTENSE erections

He found it deep in the jungles of the Kon Tum region when he was fighting there.

And he noticed that, whenever he ate this food, he got huge engorged erections and could last for hours.

Now today, at quite an old age, he’s still using it to perform like a young man in bed.

Here it is – this strange Vietnamese secret found in the jungle…

———-

This natural acid enhances cognitive function in men

Glutamate is officially recognized as a neurotransmitter central to cognition.

Indications of its nootropic effects were observed decades before its receptors were discovered.

As early as the 1930s and 1940s, glutamic acid acquired a reputation for improving the cognitive status of both lab rats and low‑IQ humans.

Some studies also reported beneficial effects in normal subjects…

But, because many low‑IQ humans were institutionalized back in those days, they made for convenient test subjects and comprised the majority of subject studies in this area.

Yet the results of these studies have always been controversial…

…with dozens of studies reporting a highly beneficial effect and others reporting absolutely null results.

William Vogel, one of the authors of a 1966 study:

“Despite recent judgements to the contrary, considerable evidence exists suggesting that glutamic acid does play a significant role in cognitive behavior.”

But there are very good reasons for this, as you will see.

The scientific controversy wasn’t just the result of “biased researchers” or “mere chance”…

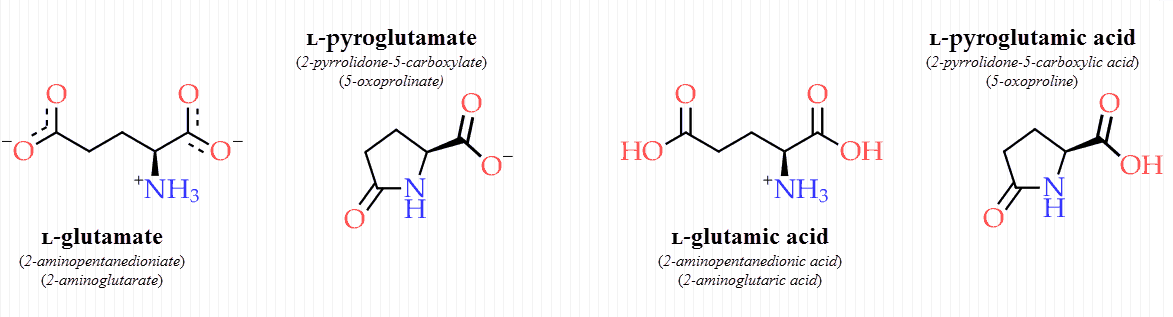

It arose primarily because of a failure to differentiate between the administered forms of glutamate/glutamic acid.

Most of the experimenters in those days were psychiatrists, not chemists…

And back then it was fashionable to use the term “neutralized glutamic acid” in lieu of the more proper “glutamate.”

This introduced confusion where there should have been none…

Because the two forms are not identical.

Although both glutamic acid and glutamate in effect would be identical upon ingestion (both becoming plasma glutamate), differences in manufacturing suggest that the more commercial glutamic acid would exist in its cyclic form:

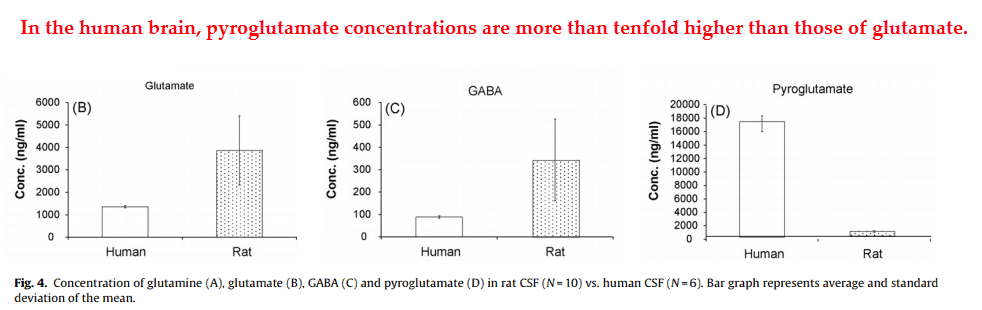

Only pyroglutamate can enter the brain, something glutamate cannot accomplish even with heroic i.v. doses.

This fact was not appreciated at the time…

It wasn’t until decades later that pyroglutamate was shown to naturally exist in the brain and to improve cognition.

In fact, the pyroglutamate concentration in the human brain greatly exceeds the concentration of glutamate:

So, although we have only a few official pyroglutamate studies to make decisions on, there are reasons to suppose that many others do exist – albeit under different headings.

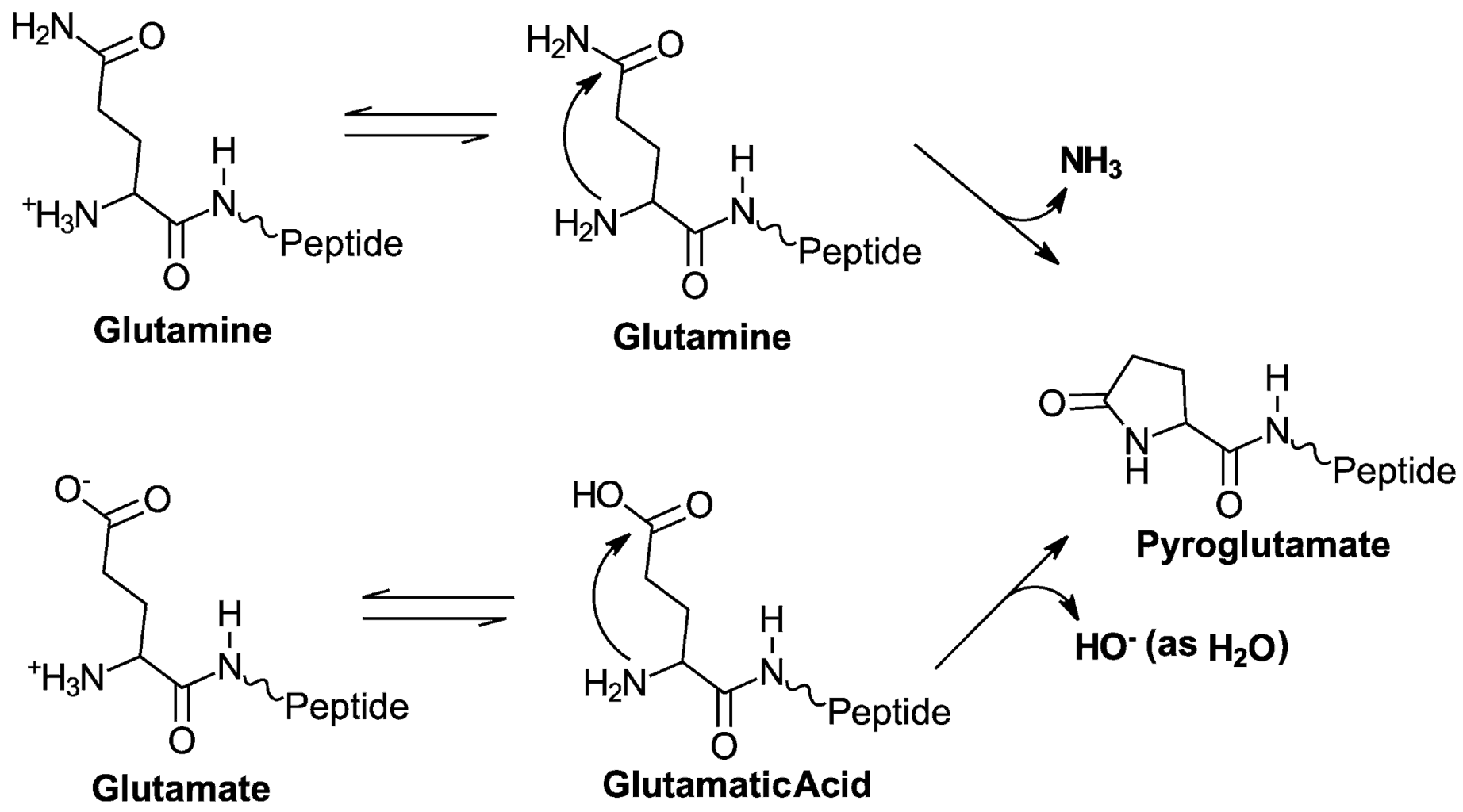

Glutamic acid spontaneously cyclicizes into pyroglutamate at low pH values (highly acidic conditions).

Although this does occur under more or less neutral conditions (e.g. pH 6-8), it occurs relatively quickly in the pH range of 2-3:

This quote is from Hildegarde Wilson in a 1937 study:

“At pH 4 or 10 the reaction proceeds to about 98 percent completion in somewhat less than 50 hours at 100°… Between pH 2 to 3 the rate is about twice as rapid…”

To convert free glutamate to glutamic acid commercially, manufacturers would have to acidify the solution down towards the same pH range where spontaneous cyclization readily occurs.

And if the solution isn’t dried immediately, you’d expect a fair amount of pyroglutamate in the final product.

Should the glutamate not be acidified, it would technically remain glutamate.

Commercial monosodium glutamate (MSG) is a different animal entirely…

By definition, it is the ionized form of the amino acid invariably found in the neutral pH range.

Monosodium glutamate also has a bound sodium ion (Na+) that prevents cyclization.

And the same can be said about the very similar potassium glutamate.

The gamma-carboxylate group needs a proton (H+) for cyclization, which can be blocked by Na+…

This is because it must leave as water for the process to occur.

[cmamad id=”26490″ align=”center” tabid=”display-desktop” mobid=”display-desktop” stg=””]

Taste is another reason why different versions of “glutamic acid” were used in the classic studies.

Pyroglutamate can be viewed as a “contaminant” in the glutamic acid test capsules that were given in high doses – often ranging between 12 and 24 grams per day.

In 1948, Doctor Frederic Zimmerman, a prolific author of a series of positive studies, remarked that the taste of “glutamic acid” was rather disagreeable:

“Glutamic acid is insoluble and has a rather unpleasant taste. Since the treatment is protracted, masking the taste properly becomes an important factor in the maintenance of regular medication.”

(A positive study in one in which the results support the hypothesis being investigated. A negative study is the opposite).

It is now known that pyroglutamate is a bitter molecule and that glutamate actually tastes good.

So, apparently, it was the inclusion of pyroglutamate that made “glutamic acid” taste bad.

And this is the very reason why approximately half of the classic glutamate/glutamic acid studies opted to use MSG instead.

Commercial glutamate and glutamic acid would be assumed equivalent by most scientists for this application…

Especially those scientists unaware of the real possibility of spontaneous cyclization during manufacturing (which also occurs on peptide ends, as depicted below).

Monosodium glutamate is currently used worldwide as a flavor enhancer, and particularly so in Asia.

MSG was discovered by the Japanese as the one component of miso soup responsible for its characteristic umami flavor…

People can now buy it by the pound in most Asian grocery stores.

Although the sodium ion would certainly contribute to the unique taste of MSG, the sodium salts of other amino acids are never used for this purpose.

There is probably a good reason for this, so we might suppose that glutamate is a particularly good‑tasting amino acid.

Pyroglutamate is also a natural component of wine, perhaps a result of the low pH and long storage times of wine.

In both wine and cheese, pyroglutamate is known to imbue a classic bitter taste.

Since pyroglutamate is also formed through glutamine, pyroglutamate can also be found in both spinach puree and beet puree.

“Sensory tasting revealed that wines containing 2 mg pyroglutamate per liter had a bitter taste as well as a bitter finish.”

“Pyroglutamic acid is thought to cause a bitter, medicinal or phenolic off-flavor in processed vegetables.”

Although this idea is somewhat revisionist, there is a considerable amount of evidence in its favor.

Nothing else seems to better explain the discordant results of the classic glutamate/glutamic acid studies than cyclization.

Moreover, how exactly can glutamic acid be expected to improve cognition despite not penetrating the blood-brain barrier?

A superficial survey of the literature presents the reviewer with this predicament…

And the most logical way out is to assume self‑cyclization during manufacturing.

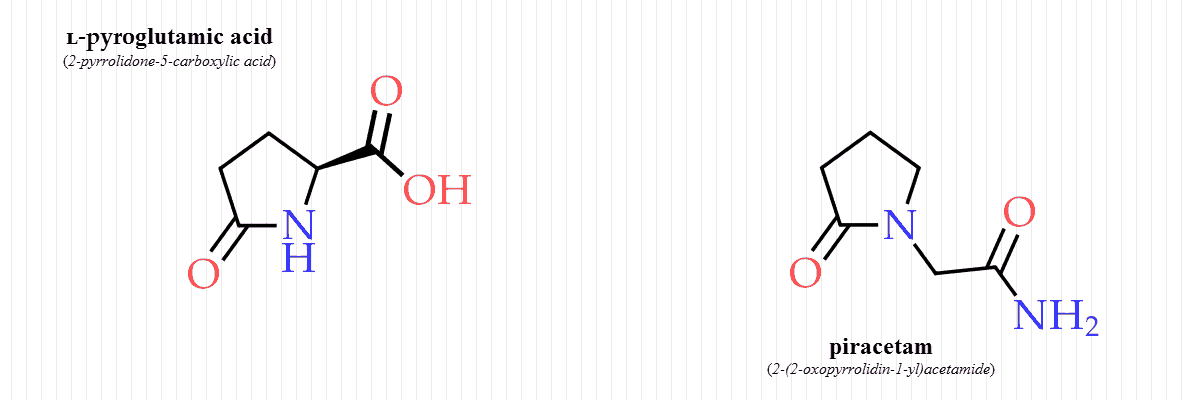

Pyroglutamic acid is also quite similar to piracetam, the original “nootropic drug.”

Both of these molecules activate the NMDA receptor, have similar pharmacokinetics, and have been shown to improve cognition.

There are so many positive studies that it would be impossible to give a full account of each.

But here are (below) a few articles that best demonstrate the controversy they’ve caused.

In this review, William Vogel starts off admonishing the authors of a previous review article on many counts.

The Astin and Ross article published six years prior was rather brief and shallow.

It left out 25 relevant studies concerned with glutamic acid and intelligence, and many well‑controlled studies were said to have “no controls.”

Yet Vogel’s article is more than simply a critique…

He included all the studies omitted by Astin and Ross (one-half the total) in his more thorough and fair analysis of the topic.

He also remarked that the positive studies were designed just as well as the negative ones if not better…

And that a few things had previously gone unmentioned that differentiated the two.

For instance, 13 of the 21 negative studies were composed entirely or nearly entirely of institutionalized subjects.

On the other hand, of the 24 positive studies, 18 were conducted using non‑institutionalized subjects.

This noninstitutionalized fraction equates, percentage‑wise, to 33% in the negative studies versus 75% in the positive.

It goes without saying that free individuals would have more opportunity for learning than those confined to institutions…

And nootropic drugs still need user input to work.

“Similarly, it is meaningless to assess the effects of a drug on intelligence with tests of specific skills and information when the subject has had no opportunity during the course of the drug administration to acquire new information or skills.”

He also found that differential dosages were used as well…

The positive studies tended more towards an individualized dosing method while the negative ones tended toward constant amounts.

The proponents of glutamic acid therapy had always stressed the individualized dosing method…

And this is because some people don’t have any effect until the higher doses are used.

In addition, some people can tolerate more glutamic acid than others due to metabolic considerations.

Things like body weight, intestinal permeability, enzyme expression, and NMDA receptor density could all be expected to influence its efficacy.

So when using a drug that has a therapeutic window, as most of them do, it is certainly more prudent to tailor the dose to each subject if positive results are desired.

“The remaining 20 [positive studies] used the individualized method of drug administration. Of the negative studies, 16 gave all subjects the same dose, while only 6 studies used an individualized method of drug administration.”

And Vogel also touches on the topic of the specific molecular form administered – i.e. whether it was “glutamate” or “glutamic acid.”

He noted that positive results came exclusively from glutamic acid, with absolutely no MSG studies showing any benefit whatsoever.

The difference between them is best exemplified by a 1951 crossover study that used both.

This study observed significant increases in IQ in the glutamic acid arm of the trial…

But after a brief washout period and subsequent MSG administration, the subjects were stuck at baseline.

Although Vogel must get credit for his other arguments and points, which were admirable, this factor is perhaps the most absolute:

“In addition, no study which used monosodium glutamate reported positive effects of the drug on the intellectual functioning…”

But Vogel had relatively little to write about this important finding, because back in 1966 there was absolutely no reason to suppose the two forms should be different.

All of that was before piracetam was popularized (1971), the NMDA receptor was conceptualized (1980), results detailing long‑term potentiation were published (1973), and pyroglutamate was known as a normal metabolite of cerebrospinal fluid (1993).

At the time, most people would surely have shrugged it off as a coincidence because no logical explanation readily comes to mind.

Back then, they explained the positive results of glutamic acid mostly through metabolic effects and choline acetyltransferase activity.

Yet the difference between forms can also be observed in the classic rat studies on glutamate/glutamic acid.

And entire thesis was written on this group of studies because of their paradoxical findings (Hughes, 1956).

Kenneth Russell Hughes focused entirely on this one topic in his early studies.

He even went so far as to breed both “dull” and “bright” rats to examine inter‑strain differences in their response to glutamic acid.

These studies were primarily inspired by the results of only two previous studies…

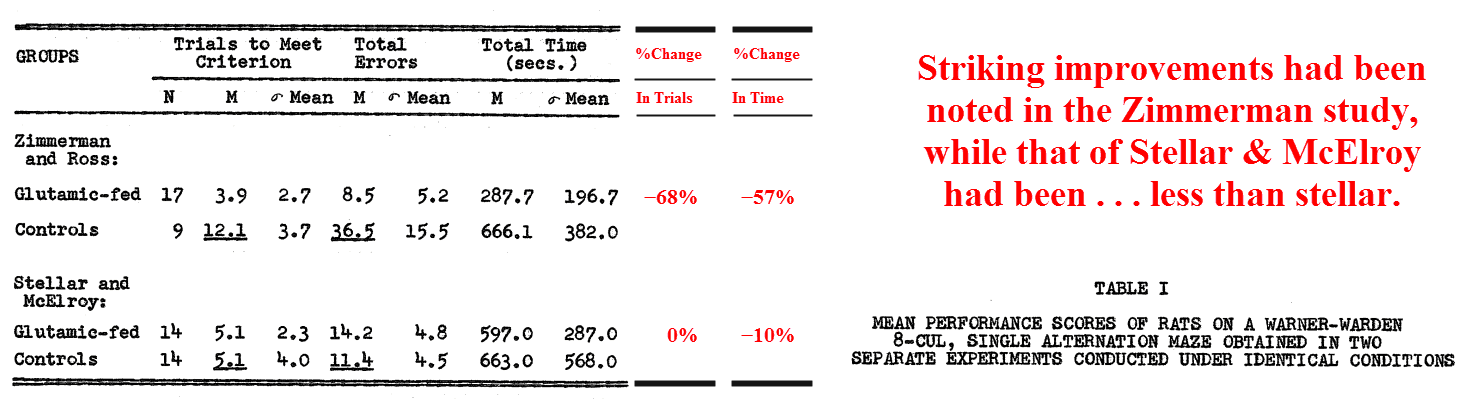

Stellar and McElroy (1948) duplicated the famous Zimmerman rat study to the T – using a perfect maze replica and the exact same study design.

The only difference of any consequence, according to Dr. Hughes, was the specific rat strains employed.

And the results of the two studies were like night and day:

It is certainly true they intentionally used a different strain of rat…

But, ostensibly, they also used a different form of glutamic acid.

But Dr. Hughes overlooked this entirely, putting all of his chips on a “ceiling effect” that prevents inherently “bright” rats from getting any brighter.

Yet the exact form used Stellar and McElroy used in their Zimmerman duplication trials is somewhat vague…

They simply used the term “neutralized glutamic acid.”

“Before each hour of daily feeding, the experimental animals were given a 5-gm dish of the basal diet, containing 200 mg of neutralized ʟ‑glutamic acid.”

To me, “neutralized glutamic acid” sounds kinda like “glutamate.”

Should glutamic acid be neutralized “in house,” so to speak, you’d expect no difference at all between the two.

Yet, had it arrived as glutamate and had Stellar decided to call it “neutralized glutamic acid” to accentuate the similarity between his experiment and Zimmerman’s (and I suspect that’s what happened), he would have a preparation entirely free of the active nootropic agent – the “contaminating” pyroglutamic acid.

Since glutamic acid is synonymous with glutamate at neutral pH by definition, a person could rationalize calling it “neutralized glutamic acid.”

Supporting this idea are the few studies published decades later using pyroglutamic acid itself, the cyclic form.

This molecule increased test scores of dementia patients (1989), and also reversed memory impairment in long‑term heavy alcoholics (1985).

From Vogel in 1966:

“Miller reported that glutamic acid led to ‘increased drive, and heightened ability to utilize one’s potential. Changes in self‑concept occur so that the person feels more competent and acts more competently.’”

So pyroglutamic acid is a veritable nootropic drug, albeit officially understudied.

It is safe, natural, available, affordable, and cannot be equated to noncyclic forms (e.g. MSG) that are incapable of crossing the blood-brain barrier.

Pyroglutamic acid can be seen as a natural version of piracetam, existing naturally in our brains already though perhaps in less than ideal concentrations.

Although it seems probable that pyroglutamic acid was responsible for the beneficial effects, there might also be some truth to the “ceiling effect.”

Like probably all nootropics, pyroglutamate should work somewhat reliably up to a point after which no further improvement can be obtained through further use.

If the normal teenage subjects of the Zimmerman study can be thought to give any indication of this, the point at which the “ceiling” is reached is at least as high as 130 IQ (1948).

Vogel in 1966 again:

“A considerable amount of evidence indicates a role for glutamic acid in cognitive functioning. The sheer weight of this evidence is surprising; indeed, there is more sound experimental confirmation of the positive effects of glutamic acid than appears to exist for the most of the psychotropic drugs now in common therapeutic use.”

—-Important Message—-

There are two ways a man can get a bigger penis…

#1. By using Big Pharma’s chemicals that make the cells of the penis swell up, putting a lot of stress on the body…

#2. By increasing the number of cells in the penis, so it grows just like muscle does.

Now, if you’re like me, you don’t want to put that stress on your body… You want to naturally and safely get bigger…

That’s why I researched some formulas that work by increasing the number of cells in the penis. And they’ve helped many of our guys here to increase their size and their loads.

All it takes is two natural ingredients and size will increase.

And sometimes a bit more goes a long way…

Here’s the size-increasing formula

———-

- Grioli, S. "Pyroglutamic acid improves the age associated memory impairment." Fundamental & clinical pharmacology (1990)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2190900 - Stellar & McElroy. "Does glutamic acid have any effect on learning?." Science (1948)

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1676737 - Hughes, Kenneth. "An experimental investigation of the effect of monosodium glutamate on the learning ability of bright and dull rats." Thesis: University of Manitoba (1956).

http://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/bitstream/handle/1993/11909/Hughes_An_Experimental.pdf?sequence=1 - Vogel, William. "The role of glutamic acid in cognitive behaviors." Psychological bulletin (1966)

http://psycnet.apa.org/record/1966-08566-001 - Wilson, Hildegarde. "The glutamic acid-pyrrolidonecarboxylic acid system." Journal of Biological Chemistry (1937)

http://www.jbc.org/content/119/1/309.full.pdf