And you may be doing this once or even 5 times a day

—-Important Message—-

How this simple shower method reverses all 3 types of “rockiness” problems

Do you know about the 3 types of “rockiness” problems?

Some men suffer from one type, some from all 3.

Unfortunately, I was one of the lucky guys to suffer from all 3 types of “rockiness” problems…

…until I discovered this simple shower method that’s not only given me back the good, strong “rockiness” I remember as a young man…

…but also increased the amount of pleasure and satisfaction I get out of sex!

———-

Men doing THIS suffer 81% more “rockiness” problems

Forget what you’ve heard about “rockiness” problems — this newsletter today will blow you away and change everything.

Let’s start here: the main risk factors for “rockiness” problems in men are generally considered to be diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and smoking.

The first two conditions are often easily fixed by increasing magnesium, a mineral that controls both the rate of sugar metabolism and blood pressure.

Most Americans don’t consume the recommended intake of magnesium as it is.

And the situation is often made worse by salt intake because sodium is known to displace magnesium from cells.

This could be why salt doesn’t increase blood pressure in everyone – and then only gradually when it does.

Ensuring an adequate magnesium intake allows one to worry little about using salt.

The latter two risk factors however, cardiovascular disease and smoking, appear not to be associated with magnesium but rather with free radicals.

Both conditions are associated with low vitamin C, a powerful antioxidant that protects against reactive nitrogen gasses.

The manner by which smoking increases the risk for “rockiness” problems initially puzzled doctors and researchers.

But within the last twenty years, the mechanism has largely been worked out.

So this article is about the evidence proving the association, the mechanism in which it occurs, and what smokers can do to counteract it.

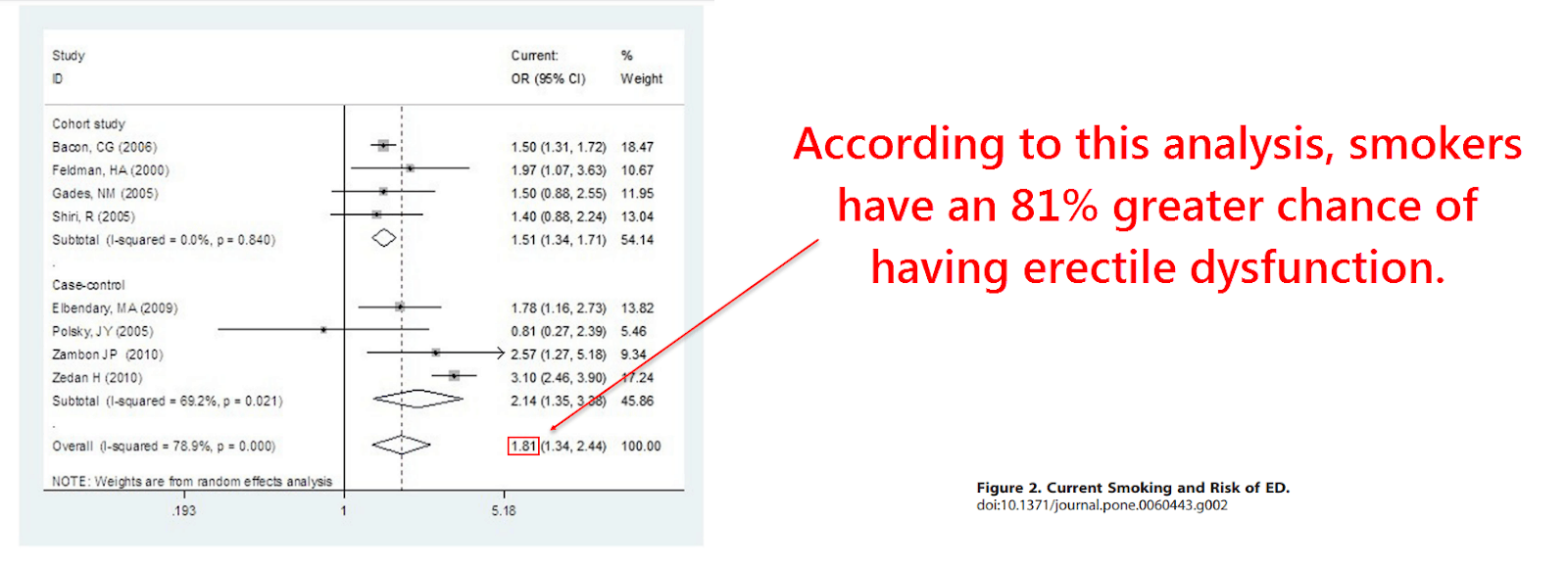

Starting with the epidemiology, the study above is perhaps the most thorough meta‑analyses ever conducted to examine the effect.

These Chinese statisticians read 3,494 individual citations during the initial screening procedure, eventually settling on just 40 for further review.

This gives us some idea of just how much evidence has been published on the smoking–“rockiness” problems link.

Of these 40 studies, they chose the eight best ones for the final analysis.

This was because they wanted large case‑control and cohort studies that could be statistically compared with each other.

They excluded all cross-sectional studies and those with weak methodology.

After they finished all the calculations, smokers were found to have a risk ratio of 1.81 of having “rockiness” problems.

This represents an 81% increased risk over the prevalence in nonsmokers:

A total of 28,586 participants from five countries were included in the final analysis, demonstrating the consistency of the effect across the globe.

The fact that smoking is associated with “rockiness” problems virtually everywhere argues towards it having a biological basis, not a cultural one.

Also supporting this finding is the large number of other studies that were not included in the analysis.

For example, below are a few other reports followed by the risk ratio for about 10 to 20 cigarettes per day and the country(s) the study was conducted in:

- Author, date ― risk ratio ― country

- Mirone, 2002 ― 1.60 ― Italy

- Austoni, 2005 ― 1.40 ― Italy

- Bortolotti, 2002 ― 1.20 ― Italy

- Chew, 2009 ― 1.69 ― Australia

- He, 2007 ― 1.45 ― China

- Lam, 2006 ― 1.47 ― China

- Millett, 2006 ― 1.39 ― Australia

- Nicolosi, 2003 ― 1.26 ― Brazil, Italy, Japan, and Malaysia

- Wu, 2011 ― 1.18 ― China

- Feldman, 2000 ― 1.18 ― China

- Parazzini, 2000 ― 1.60 ― Italy

- Blanker, 2001 ― 1.60 ― The Netherlands

So the effect would seem to be rather consistent, to say the least.

This is not likely to be the result of publication bias either.

That’s because studies conducted for other reasons that don’t even mention the word “smoking” in the abstract incidentally report similar findings.

“We could find no discernable influence of publication bias. That is, articles that featured smoking in the abstract were no more likely to report data consistent with a link…” (Tengs, 2001)

So this is most likely a real effect. But it still cannot tell us if smoking causes impotence or the converse.

There’s always the possibility, however remote, that impotent men tend to smoke more for whatever reason.

But the observation that most smokers begin smoking before the age of 18 would argue against that idea.

But we don’t have to speculate further because we now have proof of causation.

There is plenty of experimental evidence that, when taken together, proves that smoking can cause reversible “rockiness” problems – and not the other way around.

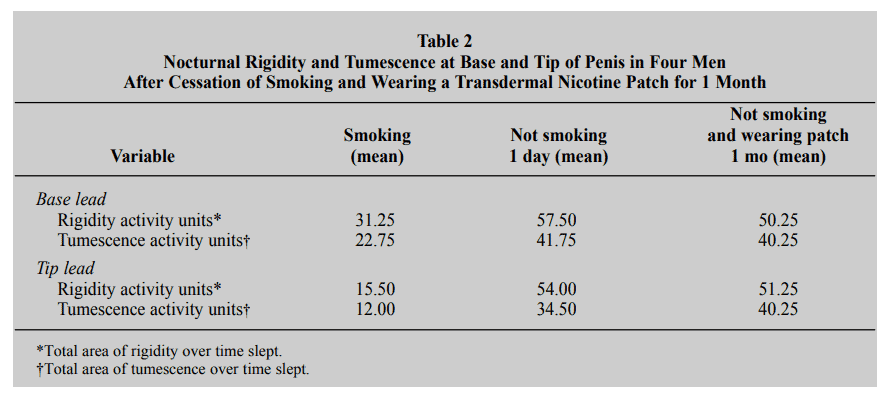

This study used ten long‑term heavy smokers with “rockiness” issues who intended to quit the habit.

Six of them went cold turkey while the other four wore nicotine patches.

The patients were taught how to use the RigiScan Plus portable home monitor, a device capable of recording penile rigidity and tumescence while asleep.

The first recordings occurred while the subjects were still smoking as usual. All subsequent recordings were taken after cessation.

They found that penile rigidity and tumescence increased just one day into quitting.

In addition, 7/10 of the subjects were finally capable of normal sexual intercourse.

Since this occurred regardless of whether the subjects wore nicotine patches or not, some other factor in cigarette smoke must be responsible…

“Xie and colleagues also believe that nicotine is not the problem.” (Guay, 1998)

“Because the improvement continues while the patient is receiving nicotine from transdermal patches, some factor or factors other than the nicotine are responsible for the erectile dysfunction.” (Guay, 1998)

This finding is also puzzling because nicotine seems like a perfect candidate.

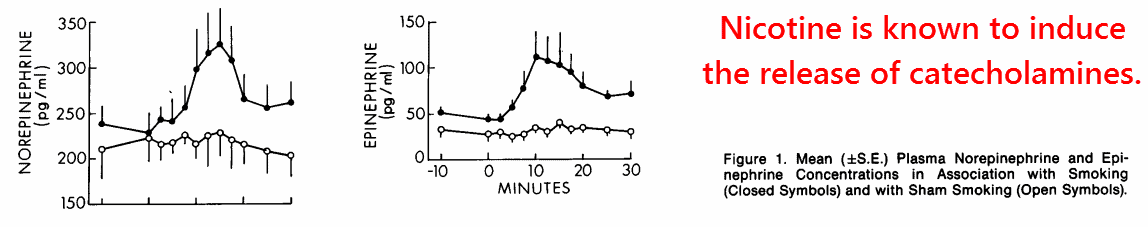

Nicotine is well‑known to release catecholamines from the adrenals that are known to inhibit erections via alpha-1- and alpha-2-adrenoceptors in the corpus cavernosum.

This is why adrenaline has been used to reverse priapism (a boner that lasts over four hours) and also why alpha blockers do the opposite and cause it.

Before sildenafil hit the market, the treatment phentolamine – an alpha-1- and alpha-2 blocker – was used to treat ED. Yohimbine is also an alpha-2 blocker.

What also makes nicotine seem like a plausible culprit is that it retains the ability to release adrenaline, even in long‑term smokers.

Yet you do see an adaptation in smokers, one that occurs on the receptor level.

Smokers have a decreased number of adrenergic receptors total, and the sensitivity of these receptors towards catecholamines is also reduced.

So even if nicotine could induce “rockiness” problems by releasing adrenaline initially, this effect should tend to diminish over time.

Yet it seems that the opposite occurs.

The “rockiness” issues caused by smoking are more consistent with a slower mechanism, a cumulative impairment seen with every decade smoked.

Also puzzling is that nitric oxide (NO), a main gas of tobacco smoke, would actually be expected to enhance “rockiness.”

This is important…

It turns out that NO is intimately involved in the mechanism behind the smoking–“rockiness” link.

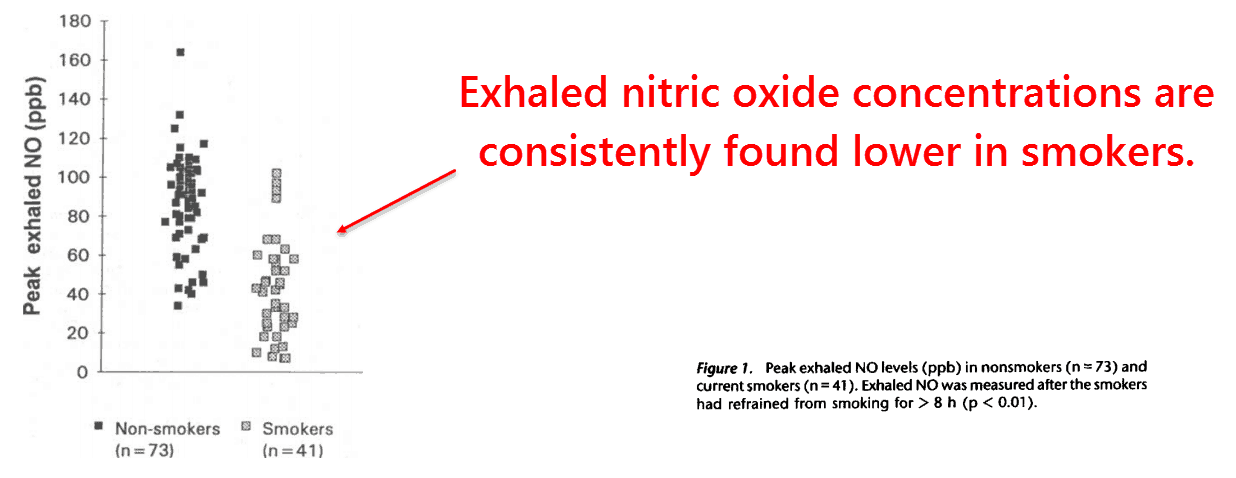

The subjects of this study were 41 cigarette smokers and 73 age-matched controls.

The researchers recorded the exhaled nitric oxide levels of each subject at baseline, compared the results, and then measured again after subjects smoked a cigarette.

They found that the NO levels of the smokers were clustered significantly lower than those of nonsmokers.

This is quite surprising considering that tobacco smoke itself contains about 300 ppm of nitric oxide.

They also found a dose‑dependent correlation between the number of cigarettes smoked per day and levels of exhaled nitric oxide.

The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated as r = −0.77, a surprisingly good fit.

A coefficient of either 1 or −1 represents a straight line connecting all dots together while a coefficient of 0 is a completely random scatter.

This effect had been confirmed one year previously by others (Bodis, 1994).

In that earlier study, the average NO concentration of smokers was found to be three times less than that of nonsmokers.

If this isn’t enigmatic enough, the study we’re discussing here found that even smoking just one cigarette would decrease nitric oxide levels even further.

“Acute cigarette smoke exposure caused a reduction in peak exhaled NO from 65 ppb to 44 ppb, which was significant, 5 min after smoking. However, NO levels returned to control values within 15 min…” (Kharitonov, 1995)

Then they tested the effects of inhaling carbon monoxide in concentrations similar to those found in tobacco smoke.

This did nothing to change exhaled nitric oxide, thus ruling out both carbon monoxide and nicotine as the cause of “rockiness” problems in smokers.

Because none of the inhaled NO had been exhaled, this could only mean that smokers have a reduction in endogenous synthesis of NO.

Exhaled nitric oxide only comes from one of three related enzymes – endothelial NOS, neuronal NOS, and inducible NOS.

So it would seem natural that attention should be focused on these.

This sounds plausible considering that NO has been shown to decrease its own production by inhibiting the very enzyme that makes it.

This could be an evolved safety mechanism to prevent high NO levels from accumulating.

“The enzyme activity of…cells was not restored after the removal of SNAP [a nitric oxide donor] by gel filtration, suggesting that NO inhibits NO synthase irreversibly.” (Assreuy, 1993)

More detailed evidence indicates that the enzyme’s cofactor, tetrahydrobiopterin, is most likely responsible for its inactivation.

Tetrahydrobiopterin is a redox‑sensitive cofactor that can be inactivated by a number of free radical gasses, including nitrogen dioxide – another component of cigarette smoke.

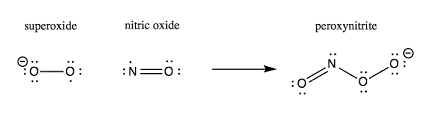

Tetrahydrobiopterin is also oxidized by peroxynitrite, a molecule readily formed by the combination of nitric oxide and superoxide.

Tetrahydrobiopterin is a necessary cofactor for NO synthesis.

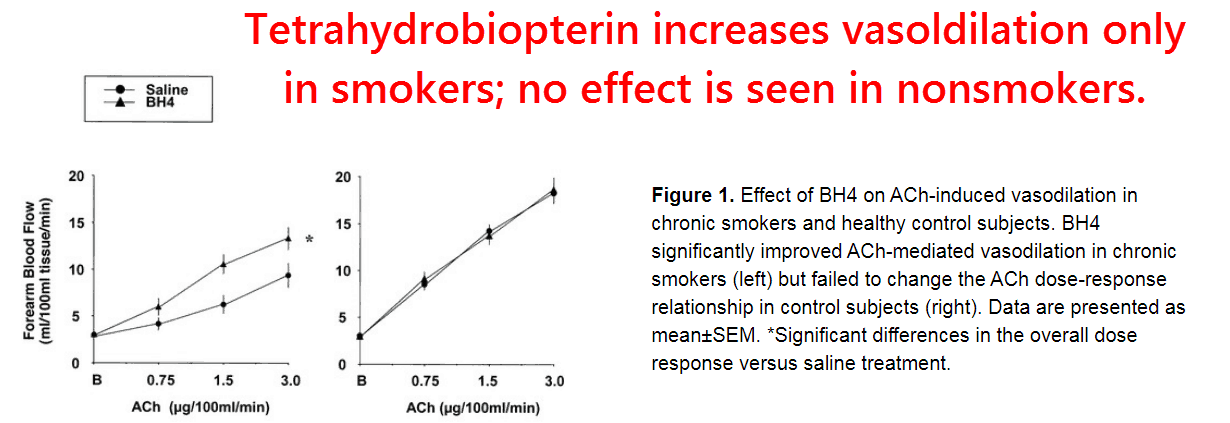

So it should be no surprise that its injection can radically induce vasodilation (dilatation of blood vessels which decreases blood pressure).

However its inactive form, dihydrobiopterin, has been shown to do the opposite by displacing tetrahydrobiopterin.

The enzyme eNOS (nitric oxide synthase 3) has been shown to have equal affinities for both tetrahydrobiopterin and dihydrobiopterin.

But only one will actually work.

For this reason, the ratio between the forms is critically important and affects enzyme activity.

The ratio of tetrahydrobiopterin to dihydrobiopterin has been proposed as a biomarker for endothelial dysfunction.

Endothelial dysfunction is a condition in which the inner lining of the small arteries fails to perform all of its important functions normally.

Since tetrahydrobiopterin is constantly being produced in the body by the enzyme GTP‑cyclohydrolase, the rate of its oxidation is the main factor in determining its concentration.

With this in mind, a groundbreaking study published 24 years ago can be seen for what it is.

It had been shown that saphenous veins from smokers, which were removed to correct varicose veins, could only synthesize 1/7 the amount of nitric oxide as those from nonsmokers.

After the addition of 20 μM tetrahydrobiopterin however, the veins from smokers produced essentially the same amount of NO as nonsmokers.

On the other hand, adding the same amount of tetrahydrobiopterin to the veins of nonsmokers did absolutely nothing.

The same effect was observed in the degree the smoker’s veins would relax in response to phenylephrine, a response severely impaired in smokers when compared to nonsmokers (27% vs. 53%).

Tetrahydrobiopterin had equalized the response completely while causing no change in nonsmoker’s veins (51% vs. 49%).

It was also shown by Western blot that the total amounts of eNOS were the same – the only difference being its activity.

“From these observations, we conclude that the concentration of venous eNOS is not reduced in smokers but rather that the activity of eNOS is impaired by smoking.” (Himan, 1996)

So it can be surmised that smoking either induces the destruction of tetrahydrobiopterin or inhibits its synthesis.

Surprisingly, there’s evidence for both mechanisms occurring…

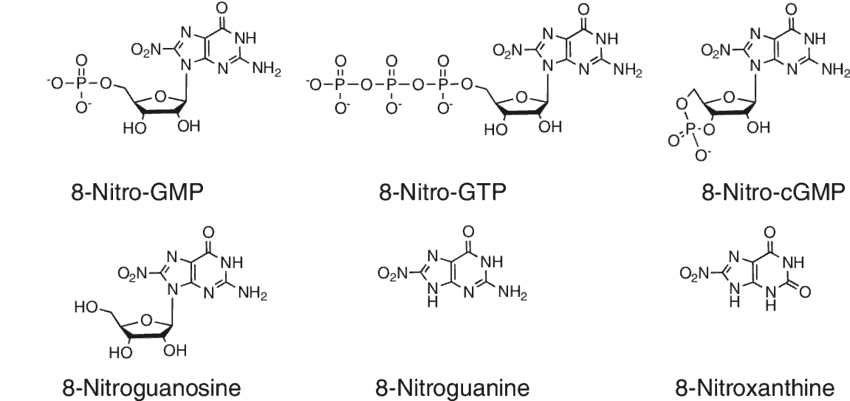

For instance, both nitric oxide and peroxynitrite have been shown to add to guanine, the precursor of tetrahydrobiopterin, forming 8‑nitroguanine.

This has been detected in the urine of smokers, and also in their lymphocyte DNA.

Yet it has also been proven that many free radicals can also damage the active cofactor itself, tetrahydrobiopterin, first by oxidizing it into trihydrobiopterin which eventually degrades into dihydrobiopterin.

Fortunately for smokers, vitamin C has been shown to revert trihydrobiopterin back into active tetrahydrobiopterin.

It is likely for this reason that vitamin C has been shown to reverse the endothelial dysfunction seen in smokers.

This effect was confirmed one year later, using both vitamin C and tetrahydrobiopterin (Heitzer, 2000):

In guinea pigs – another animal that cannot synthesize its own ascorbate – the administration of vitamin C has been shown to increase the tetrahydrobiopterin to dihydrobiopterin ratio.

Vitamin C has also been shown to increase concentrations of tetrahydrobiopterin and nitric oxide in umbilical vein endothelial cells, aortic endothelial cells, and apoE‑deficient mice.

So, when taken together, the available evidence paints a clear picture of how smoking causes endothelial dysfunction – and also erectile dysfunction:

The free radicals nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, and peroxynitrite in tobacco smoke inactivate tetrahydrobiopterin and modify its precursor.

Since tetrahydrobiopterin is difficult to come by and vitamin C is dirt cheap, it could be a good idea to supplement C.

We also need vitamin C for collagen synthesis.

And because of the free radicals, plasma levels of collagen are consistently found lower in smokers.

Smoking a lot is probably a bad idea — but if you do smoke, vitamin C can be very helpful and protective.

I find vaping, pipe smoking, or cigars is probably safer than a bunch of cigarettes.

Vitamin C can help even more.

—-Important Message—-

Special form of vitamin C increases penile blood flow

I’m now using Super C, and it’s making regular vitamin C obsolete…

See, the problem with regular vitamin C is that it doesn’t stay in the body long enough…your body eliminates it in under 5 minutes (as you can see when you pee).

But my new Super C stays in the bloodstream for HOURS, not minutes.

And more than that, it penetrates and helps cells in the brain, testes and organs.

It is constantly delivering incredible benefits:

- Making you more immune to sickness (and reducing gut endotoxins, boosting T and shrinking an inflamed prostate)

- Increasing penile blood flow for better “rockiness”

- Reducing inflammation by up to 45%

- Naturally lowering blood pressure

- Even helping to raise your natural immunities to the dreaded virus

- …and much more…

Discover my new Super C and all the benefits here

———-