This one nutrient can also reverse blood sugar symptoms… here’s how…

—-Important Message—-

“Like getting testosterone injections but better”

In just 5 minutes, you can whip up a natural testosterone booster that starts working immediately, whenever you need it.

And can take these little T boosters with you on the go, so anytime you want a boost in confidence or a little extra “oomph” down below…

…you just pop one of these T boosters in your mouth…

One man said: “It’s like getting testosterone injections but better”

Here’s how to get the effects of T injections at home (naturally and safely)

———-

Shocking proof that this one thing leads to blood sugar problems in men

The body of evidence linking magnesium to blood sugar problems is very consistent, convincing, overwhelming, and an entire book would be needed to do it justice.

The ability of humans to utilize glucose has been linked to its intake, whole serum levels, intracellular levels, and the concentration found in bone.

Supplementation has also been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in humans, sheep, and mice.

Moreover, experiments done in vitro are entirely consistent with magnesium’s pro‑metabolic role.

Insulin has been shown to specifically induce the uptake of Mg2+ from the extracellular space, and once inside the cell it correlates perfectly with glucose metabolism.

And considering that magnesium is a cofactor for over 300 human enzymes, many of which are related to diabetes, it should be no mystery how it does what it does.

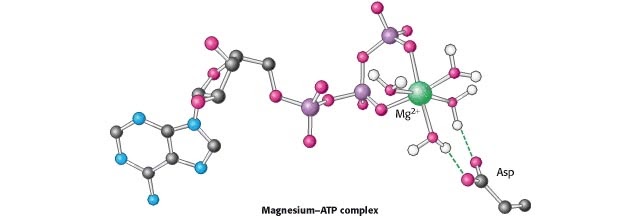

Although magnesium is a protein‑bound coenzyme for a handful of enzymes — e.g. enolase, glutamine synthetase, ribulose‑1,5‑bisphosphate carboxylase — it also increases the rate of many others through ATP.

This is because the Mg2+ ion is unique in its affinity for ATP, forming a strongly‑bound complex called Mg2+-ATP.

This is the true cofactor for hundreds of enzymes, not ATP per se.

Most of the enzymes involved in glycolysis utilize a Mg2+-ATP cofactor and the final step of the pathway, enolase, also requires a bound magnesium ion.

“[…] seven of the 10 enzymes involved in the catabolism of glucose or glycogen to pyruvate by the glycolytic pathway are activated by magnesium, including phosphofructokinase and pyruvate kinase, which are the two main regulatory points in the pathway.” ―Sigel, 1990

In addition to seven of the enzymes in the glycolytic pathway, four Krebs’ cycle enzymes also require magnesium…

Pyruvate dehydrogenase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, and succinyl-CoA synthetase.

This means that just over half of the 20 enzymes that are most involved in metabolizing glucose require magnesium, most in the form of the Mg2+-ATP complex.

So after considering the prime role of magnesium in sugar metabolism, it should be no surprise that so much evidence has linked it to diabetes type‑II.

Although a full account would take more than this short article, I’ll do my best to highlight its importance:

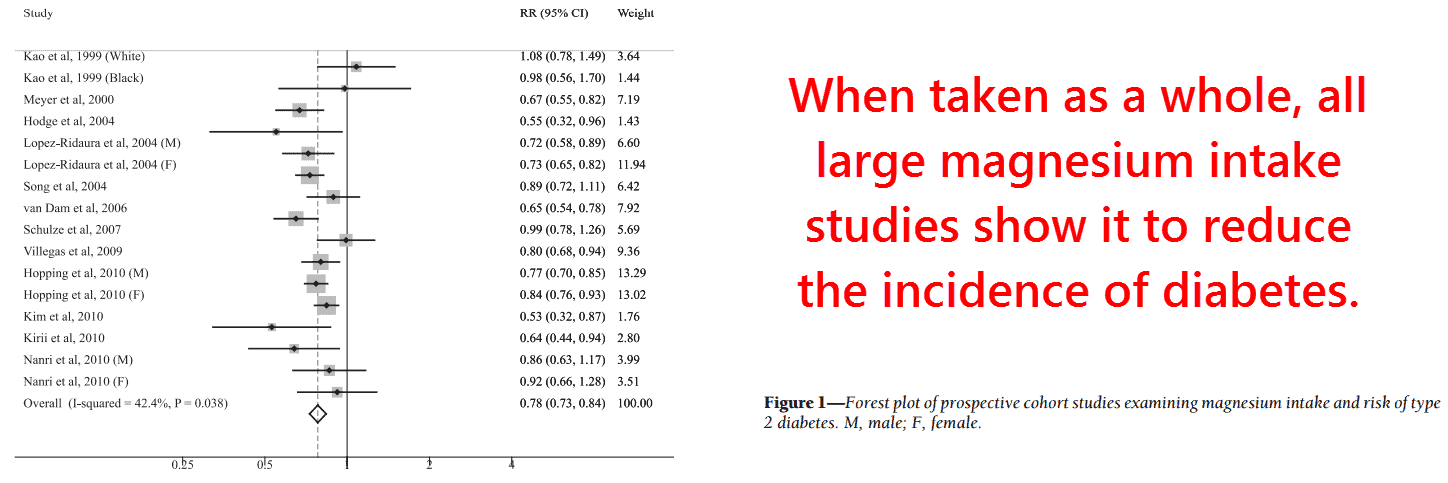

On account of there being so many studies on Mg2+ intake and diabetes to choose from, it’s perhaps best to simply use the most comprehensive review article.

This study had compiled the results of 13 prospective studies conducted in the United States, Asia, Europe, and Australia.

A total of 536,318 participants were ultimately included in the final analysis, so the results were statistically significant to say the least.

The final number arrived at was a risk ratio of .78 after comparing the highest Mg2+ intakes to the lowest.

Keep in mind that everybody consumes at least some magnesium, so you might not expect an alarmingly wide margin.

And of course, there are other causes of diabetes type‑II: Low bile production, omega-6 fatty acids, riboflavin deficiency, and hypothyroidism are just a few.

Nonetheless, what the data lacks in shock value it makes up for in consistency.

All the studies but one had shown approximately the same effect: a modest reduction in diabetes going with the higher intakes…

The only study which DIDN’T show an effect was merely three years in duration and focused more on cardiovascular disease.

For this reason, they had used a short 61‑item Willett questionnaire specifically tailored towards estimating lipid intakes — not minerals.

Regardless: the only study not showing a correlation to Mg2+intake contradicted itself by demonstrating a strong correlation with Mg2+serum concentrations, a more reliable value to say the least.

“Among white participants, low serum magnesium level is a strong, independent predictor of incident type 2 diabetes.” ―Kao, 1999

Serum magnesium values don’t lie, and we all know how subjects tasked with self‑reporting their food intakes often get selective amnesia.

This takes us to studies using more reliable assessments of Mg2+ status, like whole serum concentrations, plasma ionized Mg2+ concentrations, bone concentrations, and intracellular Mg2+ concentrations:

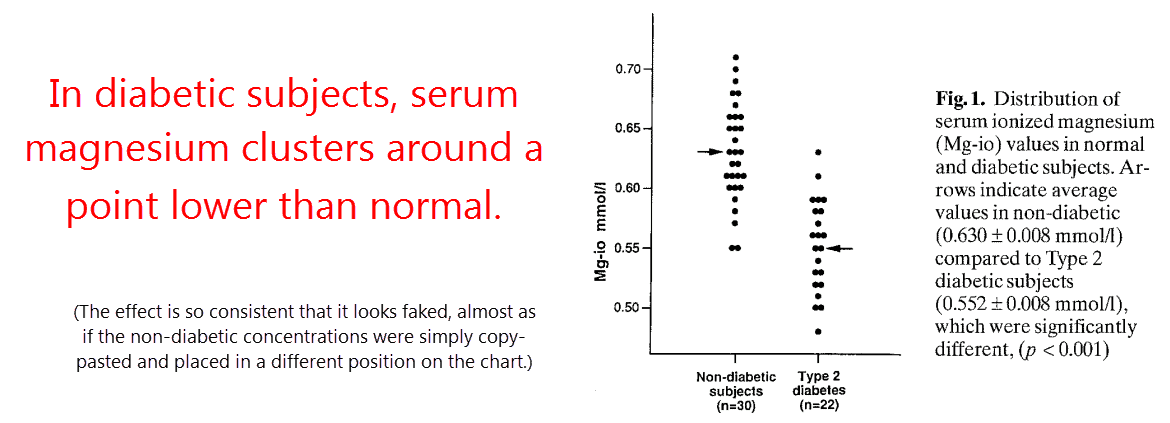

This is an early study by Lawrence Resnick, MD, a medical doctor who pioneered new chemical methods for determining Mg2+ concentrations inside of cells.

This turned out to be an important factor.

Magnesium concentrations in the plasma generally exceed the amount needed for efficient glycolysis, yet Resnick was the first to show that intracellular Mg2+ exists in the regulatory range.

“Contrary to what had been suspected, Mgi [intracellular Mg2+] exists in the regulatory concentration range for most magnesium-dependent enzyme, channel, and pump mechanisms.” ―Resnick, 1993

And because approximately 65% of whole‑body magnesium exists in the bone where it’s exchangeable with plasma levels, thus buffering its concentrations…

The amount actually contained within the cells is a more accurate index of true Mg2+ status.

And moreover, all subjects in this study were diagnosed on the spot upon having their blood glucose and HbA1C measured.

So not only is this study particularly reliable because it measured intracellular magnesium, but also because blood sugar was measured simultaneous with it.

In other words: “diabetics” that were diagnosed previously may not actually have diabetes at the moment their plasma Mg2+ is determined.

This study transcends this objection by matching blood glucose to intracellular Mg2+ concentrations temporally, a practice making it especially convincing.

And the correlation found was completely unambiguous.

Besides the difference in ionized serum values found (.630 versus .552 mmol⁄L), intracellular magnesium showed an even greater reduction in newly‑diagnosed diabetics (.223 versus .184 mmol⁄L).

So if you were to plot intracellular magnesium against blood glucose you’d probably get a straight line, though Resnick failed to do that.

Diabetes defined by him was an either/or proposition, the cut‑off value being 7.8 mmol⁄l.

“These data suggest the overall notion that magnesium deficiency, defined on the basis of either intracellular levels or serum ionized magnesium concentrations, is a common, if not universal feature of the diabetic state.” ―Resnick, 1993

The study design used also defies speculation that diabetes causes hypomagnesemia and not the other way around.

This was a popular idea in the early days, but no longer holds up after newer studies such as this.

What completely destroys that contention more than anything are studies showing magnesium restriction can actually cause diabetes.

You heard that right. Magnesium restriction has been shown to cause diabetes in rodents, sheep, and humans — of course impossible if it was merely a symptom of it.

It has also been proven that fructose‑induced diabetes is truly caused by low concentrations of Mg2+ found in high‑fructose chow blends, not fructose itself.

“In conclusion, the present study clearly shows that magnesium deficiency and not fructose ingestion per se leads to insulin insensitivity in skeletal muscle and elevations in blood pressure in rats.” ―Balon, 1994

So there is no way to argue out of the fact that low magnesium causes diabetes.

Dietary intake studies, intracellular Mg2+ determinations, and even restriction diets all lead to the same conclusion.

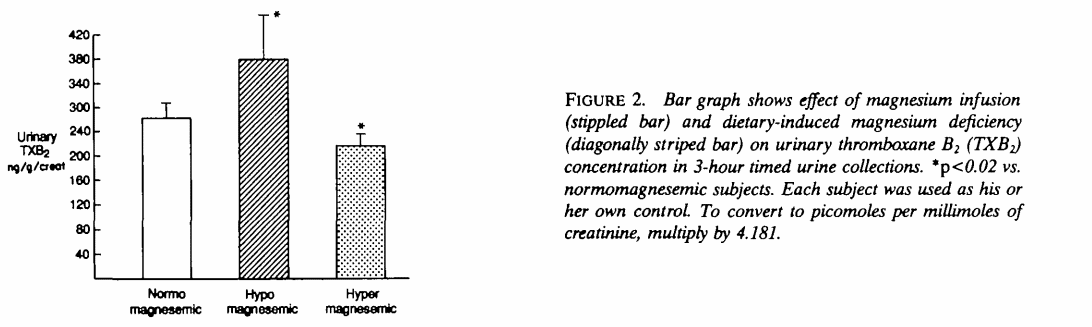

And moreover, low magnesium also increases aldosterone levels and thromboxane synthesis:

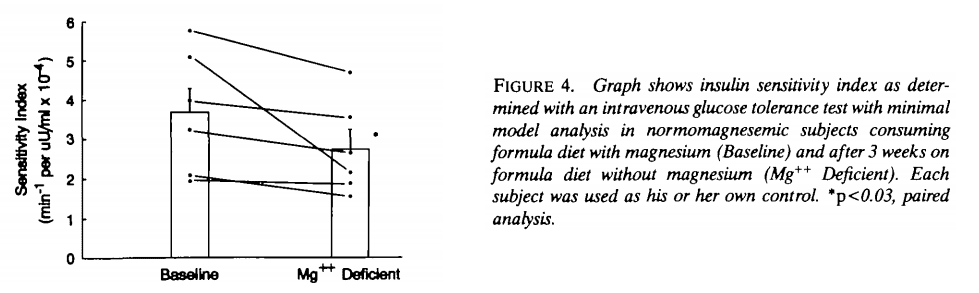

This study was done by giving sixteen human subjects a low magnesium diet for four weeks. They were all apparently healthy, within 120% of normal body weight, and were American.

The diet had contained only 12 milligrams of magnesium as determined by flame spectroscopy.

To put this low value into perspective, the current RDA for magnesium is set at 400 milligrams per day for men.

After the four week restriction period, the subjects underwent a glucose tolerance test. This basically entails injecting glucose and measuring how long it takes until it disappears.

By taking blood samples at three time points before injection…

And then 26 more within the three hour period afterwards…

They were able to calculate an “insulin sensitivity index” using their repeated plasma glucose and insulin measurements..

And consistent with all previous data on Mg2+ and diabetes, these researchers showed the expected result.

At the time the subjects’ glucose handling was calculated, their intracellular magnesium dropped from 186 to 127 millimole per liter:

So it’s official: Low magnesium causes diabetes and not the other way around.

In addition to this, the low magnesium diet literally doubled aldosterone concentrations (18 versus 37 ng⁄dL).

This is perhaps not surprising for a common mineral — sodium restriction would do the same.

Yet completely unexpected was the finding that magnesium restriction had increased thromboxane A2 and B2 concentrations.

These are both technically prostaglandins, and had been named for their ability to aggregate platelets and form thrombii.

So not only has low magnesium been firmly linked to diabetes, it also conspires with omega-6 fatty acids to cause ischemic heart disease.

So we should not forget about consuming magnesium, a mineral so many common foods are deficient in.

Most people tend to focus more on their intakes of sodium and calcium, but ions K+ and Mg2+ should also be considered.

So how much magnesium to take? Is the current RDA of 400 milligrams per day set to low or sufficient to prevent disease?

Well the meta‑analysis that included over half a million subjects analyzed studies comparing intake levels of, on average 391 versus 214 milligrams per day (Dong, 2011).

The average intake in white American males as of fifteen years ago was estimated at 237 milligrams per day (Ford, 2003).

So by those standards, 400 milligrams per day would appear largely protective against diabetes.

However, studies giving people higher amounts have consistently been shown to be beneficial:

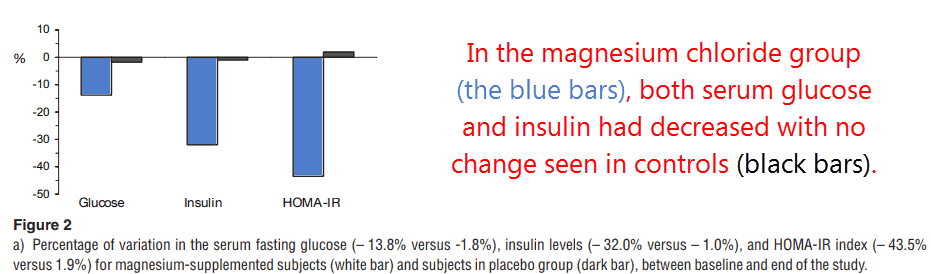

This Mexican study took 32 people and gave them 2.5 grams of MgCl2 per day, an amount corresponding to 638 milligrams of magnesium and 1,862mg of chloride.

Six‑hundred and thirty‑eight milligrams is a fair amount of magnesium, approximately threefold more than the average intake in Mexico of 215 mg⁄day (Mejía-Rodríguez, 2013).

The results were impressive after twelve weeks, with a 32% reduction observed in plasma glucose despite a 44% lowering of insulin.

From this data, it can be inferred that magnesium increased insulin sensitivity:

So at this point, magnesium’s role in glucose metabolism is becoming evident.

Its utility in diabetes is something you could bet the farm on, but how exactly does it accomplish it?

As alluded to before, magnesium increases the rate of the majority of glycolytic and Krebs’ cycle enzymes.

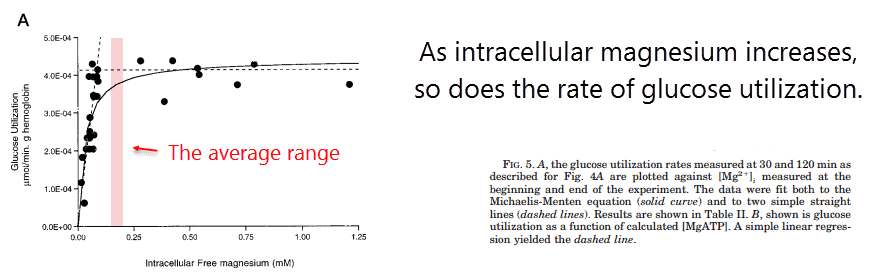

This has been proven in studies on each individual enzyme, and magnesium has also been shown to enhance whole‑cell metabolism:

This study determined free Mg2+ inside of human red blood cells like Resnick’s, yet went one step further.

These scientists ultimately showed, by changing concentrations of intracellular Mg2+, that glycolytic flux was highly dependent on the element.

Even though most everyone should enough intracellular magnesium to achieve a 75% efficiency, at least in erythrocytes, getting that extra boost would require an RDA‑sized daily intake or higher:

And of course this says nothing about the magnesium found within adipocytes or neurons.

Since the bones release magnesium the moment serum concentrations fall, it can be assumed that red blood cells would contain some of the highest amounts.

The concentrations of Mg2+ in other cell types could be far lower, which unfortunately could only be determined through invasive biopsies.

Yet experiments show that supplemental magnesium is safe throughout the milligram range.

And to further highlight its importance, magnesium appears necessary for insulin action.

As early as 1960, magnesium was the sole ion found to be required for insulin‑mediated glucose uptake:

“The Mg2+ ion is of particular interest in this respect. The presence of a low concentration of Mg2+ ions enabled the diaphragm to respond to insulin under ionic conditions in which otherwise there was little or no response.” ―Bhattacharya, 1960

Shortly thereafter, insulin was shown to induce the influx of Mg2+ into the cell (Lostroh, 1972).

And considering that intracellular Mg2+ concentrations fall within the regulatory range, this fact alone could probably explain the hormone’s effect.

—-Important Message for Men With Blood Sugar Problems—-

This special breakfast can eliminate blood sugar problems in 2 weeks

It costs less than $1 to make, and it only takes a minute.

Men are using it to reverse blood sugar problems in as little as 2 weeks — and some are reporting a big boost in testosterone too!

That’s how you know it’s working, when blood sugar normalizes, symptoms disappear, and testosterone starts climbing.

———-